Video Nasties: The Films, The Bans, The Outrage

INTRODUCTION: Rewind to Rage

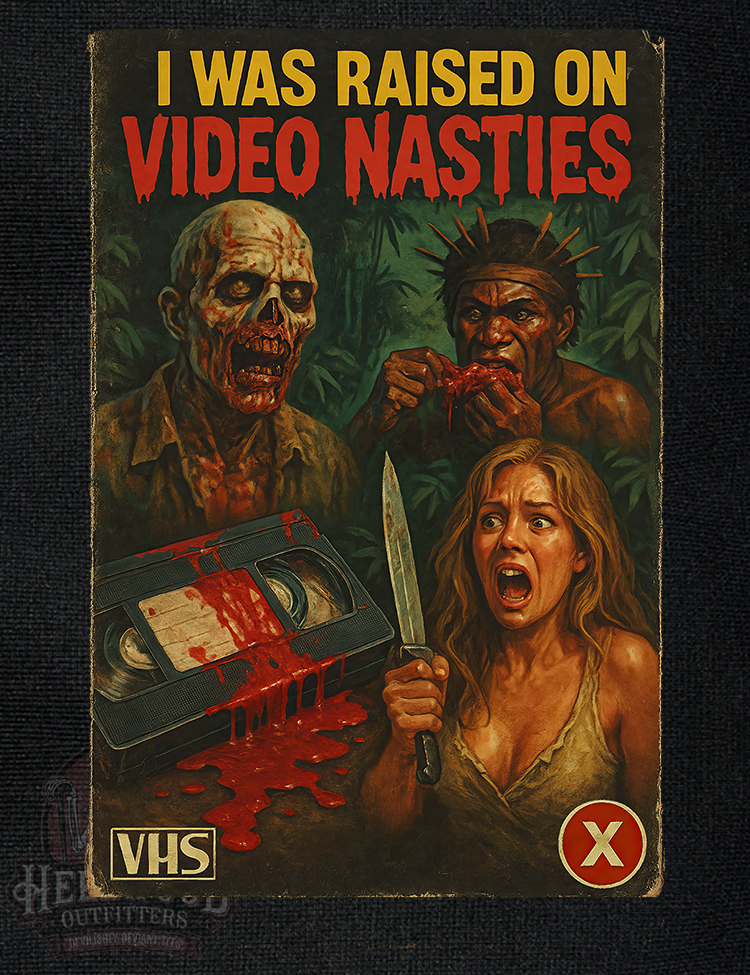

The video shop wasn’t just a place to rent E.T. or Ghostbusters—in early 1980s Britain, it became a gateway to something far more dangerous, or so the tabloids claimed. As VHS technology exploded into homes, a shadow market of lurid, blood-soaked horror tapes crept onto shelves, often sporting hand-drawn covers more terrifying than the films themselves. With names like Driller Killer, Cannibal Ferox, and I Spit on Your Grave, these films didn’t just promise fear—they threatened to unleash it.

Dubbed “video nasties” by a scandal-hungry press, these low-budget exploitation flicks found themselves at the center of a moral panic that gripped the UK. Politicians fumed, police raided shops, and headlines warned of the mental destruction of the nation's youth. What began as a niche horror movement mushroomed into a national obsession—and a government crackdown.

This article explores the hysteria, the history, and the horror. We’ll examine which films made the Director of Public Prosecutions’ hit list, why they were banned, who was behind the outrage, and how these so-called “nasties” refused to stay buried. Buckle up: the VCR isn’t just rewinding—it's dragging us straight into the belly of Britain’s censorship war.

SECTION I: The Dawn of the Nasty — What Was a ‘Video Nasty’?

To understand the storm that was the video nasty panic, we need to rewind to the early days of the home video revolution. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, VHS tapes offered something radical: the ability to watch movies at home, uncensored and unregulated. For horror fans, it was a blood-drenched buffet of exploitation cinema that had never touched British cinemas—often for good reason.

The term video nasty wasn’t coined by critics or fans, but by the outraged British press. It referred to a group of films—mostly low-budget, high-gore horror and exploitation titles—that were sold on VHS without a cinema release or official classification by the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC, later renamed the British Board of Film Classification). These were raw, unfiltered, and, in the eyes of some, morally corrosive.

The problem was legal as much as it was moral. At the time, the BBFC had no authority over home video releases. This regulatory loophole allowed distributors to import and sell tapes that would never have passed a theatrical censorship board. As long as the packaging didn’t trigger obscenity charges under the Obscene Publications Act, these titles could slip into homes across the UK. For some, it was freedom of choice. For others, it was cultural poison.

Enter Mary Whitehouse—the conservative morality crusader who had long fought what she saw as the degradation of British culture. As founder of the National Viewers' and Listeners' Association, Whitehouse viewed these tapes as the latest threat to decency. Backed by tabloid outrage and moral panic, her campaign gained serious traction. Soon, pressure mounted for official censorship of home video content. The resulting crackdown would define an era—and make these obscure films infamous.

From media demonization to parliamentary debates, the phrase video nasty became shorthand for everything wrong with society’s declining moral standards. But beneath the controversy was something more complex: a battle over who controls what we see, what we fear, and what we’re allowed to enjoy.

SECTION II: The List That Launched a Thousand Seizures — The DPP’s 72

In 1983, the British government’s response to the rising hysteria over violent horror films took formal shape with the creation of the Director of Public Prosecutions’ (DPP) “video nasties” list. It wasn’t just a guideline—it was a blacklist. Comprising 72 films suspected of violating the Obscene Publications Act, the list became a cultural flashpoint, an unofficial death sentence for any title unfortunate enough to make the cut.

Of the 72, 39 films were successfully prosecuted as obscene and were effectively banned, with possession and distribution carrying legal consequences. The remaining 33 were either dropped from prosecution or eventually passed by the BBFC with significant edits—or, in rare cases, uncut. The DPP’s list wasn’t compiled through careful film critique or legal clarity. It was often based on cover art, hearsay, or a single viewing by an overworked official.

A few of the most infamous titles include:

|

Film Title |

Prosecution Status |

Current BBFC Classification |

|

Cannibal Holocaust |

Prosecuted |

18 (uncut, with animal cruelty warning) |

|

I Spit on Your Grave |

Prosecuted |

18 (uncut as of 2020) |

|

The Last House on the Left |

Prosecuted |

18 (uncut) |

|

The Driller Killer |

Prosecuted |

18 (uncut) |

|

The Evil Dead |

Not Prosecuted |

15 (uncut) |

|

Tenebrae |

Dropped from list |

18 (uncut) |

|

SS Experiment Camp |

Prosecuted |

Banned until 2005, now 18 |

|

Island of Death |

Prosecuted |

18 (uncut) |

|

Faces of Death |

Prosecuted |

Banned in UK (unclassified) |

|

The Beast in Heat |

Prosecuted |

Unclassified, still effectively banned |

The notoriety of these films was amplified not by their artistic merit but by their infamy. Some were banned more for what people thought they contained than what actually appeared on screen.

SECTION III: The Crimes of Celluloid — Why Were These Films Banned?

What, exactly, did these films do to earn their spot on the DPP's blacklist? The answer is a cocktail of horror tropes, exploitative content, and very real social fears.

Graphic Gore & Realism

Movies like The Burning and Zombie Flesh Eaters didn’t just feature violence—they showcased it with gruesome flair. Tom Savini’s makeup effects in The Burning, for instance, were so disturbingly realistic that censors feared their psychological impact on young viewers. In an era before CGI, this kind of visceral carnage hit harder—because it looked real.

Sexual Violence

Perhaps the most controversial element in the nasties was their depiction of rape and sexual torture. I Spit on Your Grave and The Last House on the Left were lightning rods for criticism, with scenes of extended sexual violence that some critics believed bordered on endorsement. Feminist scholars were split—some saw them as brutal revenge fantasies; others viewed them as exploitation in its rawest form.

Animal Cruelty

Several titles, especially from the Italian cannibal subgenre, contained actual animal killings caught on film. Cannibal Ferox and Cannibal Holocaust featured real animal deaths staged for the camera, a practice that pushed even hardened horror fans over the edge. These scenes violated not only moral boundaries but also existing animal welfare laws, making them instant targets for seizure.

Obscenity & Sadism

Many of the banned films fell into the category of "sick cinema"—gratuitously sadistic and perverse content created for shock value. These films were accused of having no artistic merit and instead of reveling in human suffering. Whether it was Nazisploitation (SS Experiment Camp) or sexually charged violence (The Beast in Heat), censors often couldn’t separate artistic intent from sensationalist filth.

Media Frenzy

Fueling the flames was a British press machine hungry for outrage. Tabloids like The Daily Mail ran front pages with headlines like “Ban This Filth!” and “Rape of Our Children’s Minds.” Politicians, eager for moral high ground, echoed the sentiment. Soon, films were being banned not on thorough legal grounds, but on the court of public opinion—trial by hysteria.

SECTION IV: Bans, Raids, and Burned Tapes — How Censorship Was Enforced

Before 1984, the home video market was a Wild West of unregulated content. But all that changed with the introduction of the Video Recordings Act, a piece of legislation rushed through Parliament in response to the video nasty panic. Suddenly, every video release in the UK had to be reviewed and classified by the BBFC. Any unclassified material was considered illegal to sell or distribute.

Enforcement was swift—and sometimes absurd. Police across the country raided video shops, private homes, and even car boot sales, seizing tapes en masse. In some cases, they didn't even watch the tapes. If it was on the DPP list, it was guilty by association.

Retailers panicked. Many pulled stock voluntarily, fearing fines or worse. This led to what critics dubbed “unofficial censorship,” where fear and misinformation led to self-policing. Some distributors edited films preemptively, releasing heavily butchered versions in hopes of avoiding legal scrutiny. Others went underground, turning the nasties into coveted contraband.

The BBFC, now tasked with overseeing not just theatrical releases but home video content, gained sweeping powers. Over time, its classification system became more consistent, but in the wake of the nasties panic, it was often guided more by outrage than reason.

SECTION V: Cult or Corruption? — The Films That Fueled the Fury

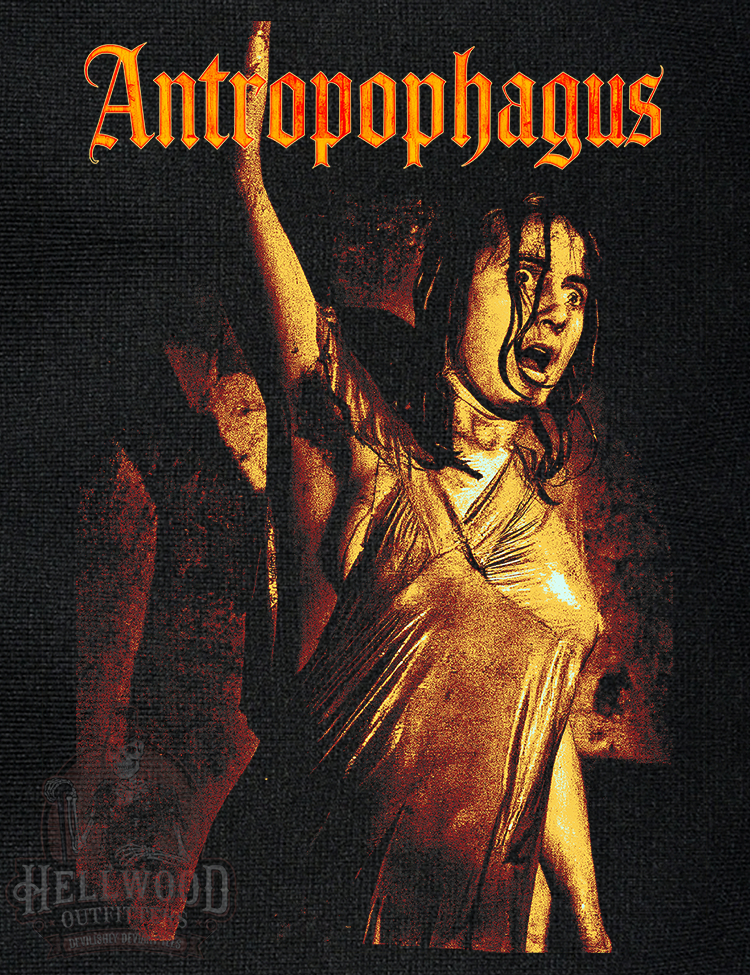

Here are 10 of the most notorious films on the DPP list—infamous not only for their content but for the controversy they inspired.

1. Cannibal Holocaust (1980)

-

Synopsis: A faux documentary follows a rescue team into the Amazon to find missing filmmakers, only to uncover a horrific reel of recorded atrocities.

-

Reason for Ban: Extreme gore, sexual violence, and real animal killings.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Condemned as obscene and snuff-like; now viewed as a proto-found footage classic.

-

Current Status: Available uncut in the UK, with warnings.

2. The Last House on the Left (1972)

-

Synopsis: Two girls are kidnapped, raped, and murdered by criminals who unknowingly seek shelter in one victim’s home—leading to brutal revenge.

-

Reason for Ban: Sexual violence, realistic tone.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Seen as repulsive exploitation; now reassessed as early Wes Craven social horror.

-

Current Status: Passed uncut by BBFC.

3. I Spit on Your Grave (1978)

-

Synopsis: A writer is gang-raped by local men and exacts violent revenge.

-

Reason for Ban: Prolonged rape scenes, perceived misogyny.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Widely reviled; now debated as feminist revenge cinema or pure exploitation.

-

Current Status: Released uncut in 2020.

4. The Driller Killer (1979)

-

Synopsis: A struggling artist descends into madness and drills his way through New York’s homeless population.

-

Reason for Ban: Gory murder scenes, especially on the infamous cover art.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Initially blamed for inciting violence; now considered gritty, low-budget psychodrama.

-

Current Status: Available uncut.

5. The Evil Dead (1981)

-

Synopsis: Friends in a cabin summon demons from the Necronomicon in Sam Raimi’s kinetic horror debut.

-

Reason for Ban: Gore, dismemberment, tree assault scene.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: A cult classic born in controversy.

-

Current Status: 15-rated, uncut.

6. The Beast in Heat (1977)

-

Synopsis: Nazis breed a feral beast-man to torture prisoners in a sadistic sex lab.

-

Reason for Ban: Sexual sadism, Nazisploitation.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Derided as tasteless trash; rarely discussed except for its infamy.

-

Current Status: Not classified in UK.

7. SS Experiment Camp (1976)

-

Synopsis: Nazi officers experiment on female prisoners in a twisted erotic war fantasy.

-

Reason for Ban: Sexual exploitation under a historical veneer.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: A lightning rod for outrage.

-

Current Status: Banned until 2005; now available with 18 rating.

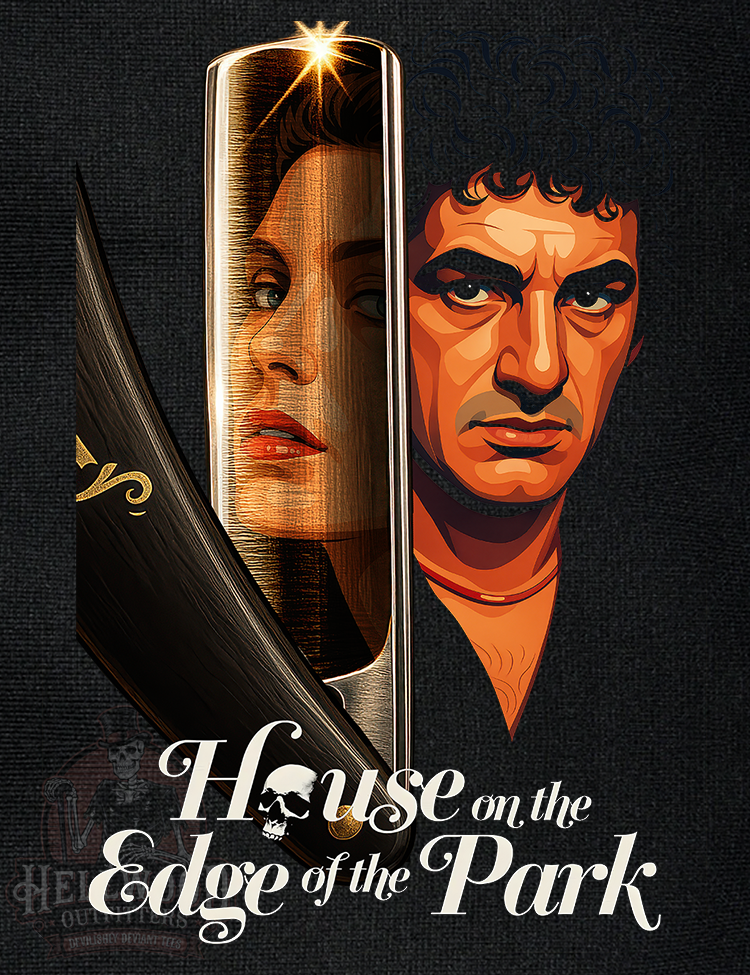

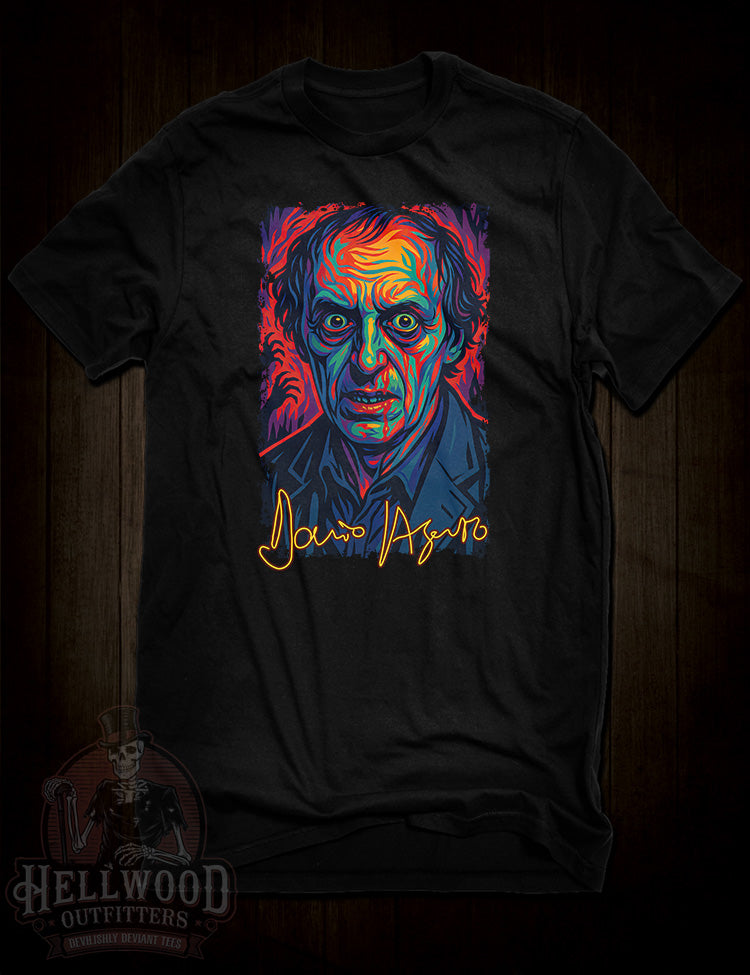

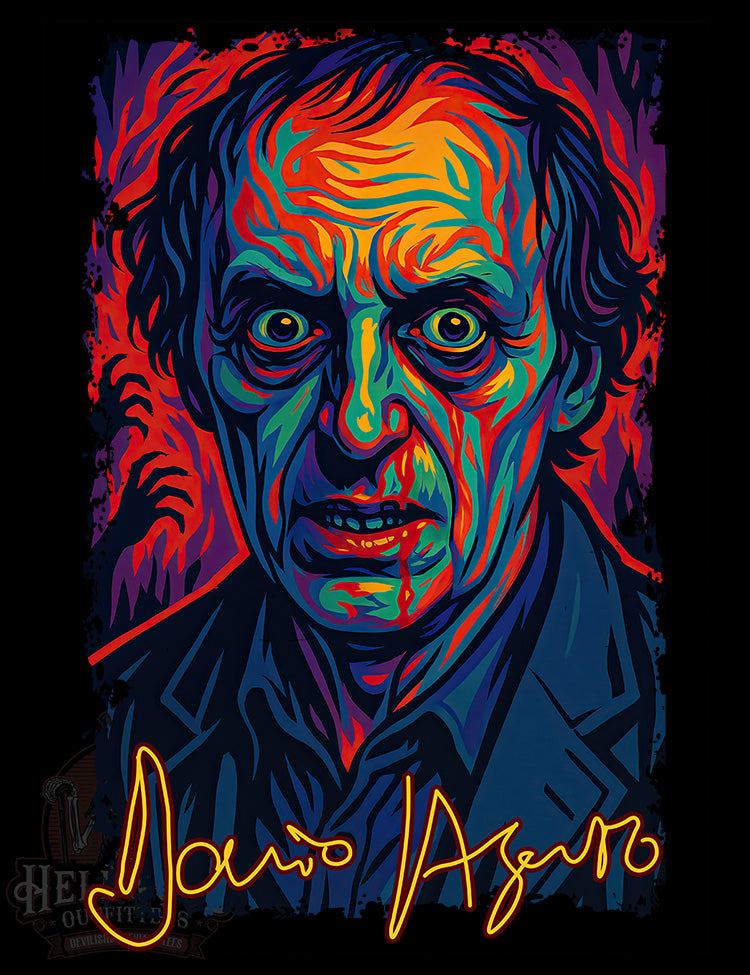

8. Tenebrae (1982)

-

Synopsis: A writer is stalked by a killer who mimics the murders in his books.

-

Reason for Ban: Stylized violence, sexualized killings.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Praised as one of Argento’s finest thrillers.

-

Current Status: Released uncut.

9. Faces of Death (1978)

-

Synopsis: A compilation of real and fake death footage presented as documentary.

-

Reason for Ban: Blurred line between fact and fiction, disturbing imagery.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Viewed as tasteless and exploitative; still controversial.

-

Current Status: Unclassified, still banned in UK.

10. Island of Death (1976)

-

Synopsis: A couple travels to a Greek island, committing a string of sadistic murders.

-

Reason for Ban: Sexually explicit violence, bestiality, homophobia.

-

Reception Then vs. Now: Once reviled, now rebranded as cult sleaze.

-

Current Status: Available uncut.

These weren’t just horror movies—they were lightning rods for an entire generation’s moral anxiety. Whether considered artistic rebellion or pure trash, they remain vital artifacts in the history of film censorship.

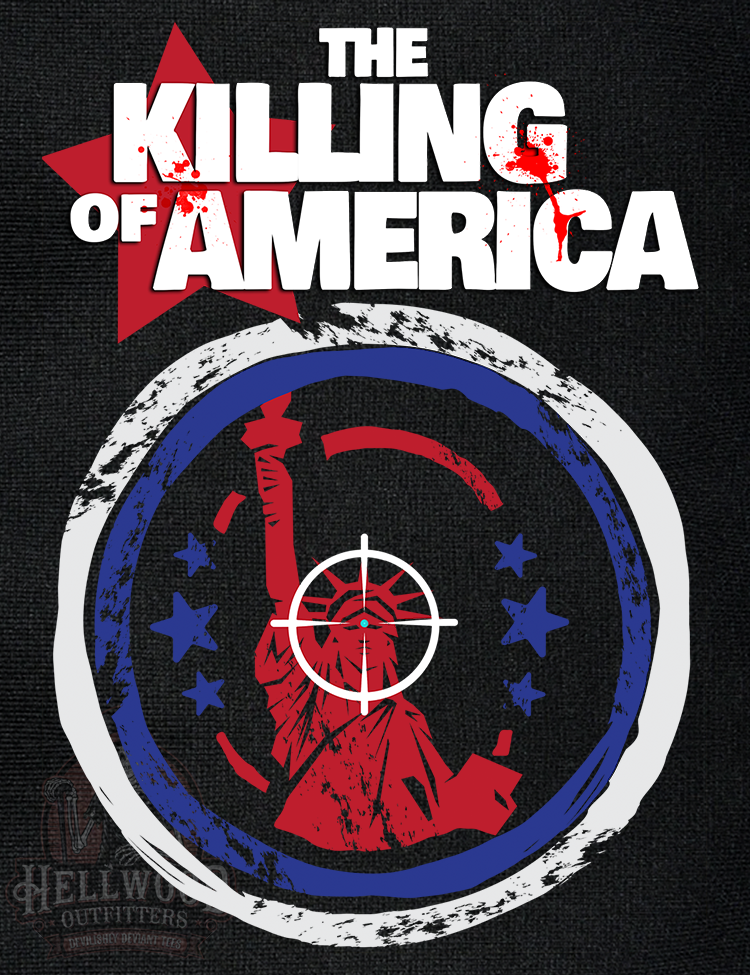

SECTION VI: The Moral Panic Machine — Culture, Fear, and the 80s Outrage

The early 1980s in Britain was a politically charged era defined by economic struggle, conservative resurgence, and a deep anxiety about moral decay. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government rode a wave of right-wing populism, championing “Victorian values” and traditional family structures. In this climate, the video nasties became the perfect scapegoat.

Thatcher’s administration viewed cultural deregulation—especially in media—as a battleground for public morality. While economic liberalization thrived, artistic expression was shackled under increasing scrutiny. Home video, with its unregulated distribution and graphic imagery, was framed not as art or entertainment, but as a threat to the nation’s moral fiber.

The media fanned the flames. British tabloids—The Daily Mail, News of the World, and others—ran headlines like “BAN THIS FILTH!” and “SICK FILMS ON SALE TO KIDS!” With little oversight or nuance, journalists painted horror fans as perverts and delinquents. Campaigners like Mary Whitehouse weaponized this outrage, lobbying Parliament and pressuring local councils to act.

The panic had a clear target: working-class youth. Policymakers feared that children, unsupervised in council estates and bedroom VCRs, were absorbing images of rape, gore, and mutilation that would warp their development. Never mind that many of these films were poorly made and barely watchable—the idea of them was enough.

In hindsight, the panic said less about the films and more about a nation struggling with rapid cultural change. The fear of juvenile delinquency, the collapse of authority, and the disintegration of traditional values found an outlet in the video nasty scare. Horror was not just horror—it was a cultural scapegoat.

SECTION VII: The Aftermath — Reappraisals, Releases, and Redemption

The dust eventually settled. The moral panic faded, but the legacy of the video nasties didn’t die—it evolved.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a critical reevaluation began. Film scholars and horror aficionados started to revisit these once-banned works, uncovering subtext, social commentary, and—occasionally—accidental artistry. Directors like Wes Craven and Sam Raimi were rehabilitated, their early films now seen as bold, if messy, milestones in genre cinema.

Restoration projects brought long-lost or heavily cut versions back to life. Film festivals like FrightFest championed these titles, screening them uncut to packed audiences. Boutique distributors (Arrow Video, Severin, Vinegar Syndrome) began issuing pristine Blu-rays with essays, documentaries, and commentary tracks that reframed the conversation.

Still, some films remain outlawed or restricted. Faces of Death remains unclassified in the UK. Others, like The Beast in Heat, are technically legal to possess but almost impossible to find in any legitimate format. Internationally, countries like Australia and New Zealand continue to apply strict content bans on select titles.

And the nasties’ DNA lives on. Modern horror franchises like Hostel, Saw, and The Green Inferno wear their video nasty lineage proudly. Eli Roth, in particular, has cited Cannibal Holocaust as a direct influence. The aesthetics—practical effects, extreme scenarios, social taboos—continue to resonate with new audiences, this time as homage rather than hysteria.

SECTION VIII: Legacy of the Nasties — What They Taught Us

The video nasties weren’t just a film classification controversy—they were a cultural lesson in censorship, freedom, and the consequences of fear.

Legally, they helped shape Britain’s modern media landscape. The Video Recordings Act of 1984 formalized the BBFC’s authority over home media, a framework that persists to this day. While it curbed the chaos, it also created a precedent for state control over private consumption.

But banning these films didn’t make them disappear—it made them legendary. The allure of the forbidden turned many into underground hits. Bootleg copies circulated, whispered about like urban legends. The act of banning them created the exact mystique that kept them alive.

There’s also a bigger truth: moral panics rarely age well. The nasties panic is now seen as a case study in overreach, where politics, media, and fear conspired to silence voices—however crude or controversial. Horror, by its nature, pushes boundaries. When society responds with repression, it often says more about our insecurities than the content itself.

Censorship advocates today should heed this history. Artistic freedom means tolerating work that offends, disturbs, or even disgusts. Horror fans, too, must balance their love of the extreme with a recognition of context, ethics, and intent. The line between art and exploitation is never clear—but silencing one to protect the other is a dangerous game.

CONCLUSION: The Nasties Never Died

Four decades on, the video nasties still matter—not just as relics of VHS horror, but as cultural artifacts of outrage, repression, and resistance.

These films were burned, banned, and belittled—but they never vanished. Instead, they survived through bootlegs, fan culture, and, eventually, official reappraisals. They remind us that fear often drives censorship more than facts, and that attempts to erase controversial art only give it more power.

Their legacy isn’t just in gore or shock—it’s in the debate they sparked. About who gets to decide what’s acceptable. About the dangers of media scapegoating. About how quickly a society can turn on its artists.

The video nasties asked, in the most brutal way possible: What are we so afraid of?

APPENDIX: The Full DPP List

(Note: Condensed for readability. Full data with legal status available via IMDb and BFI links.)

(Complete alphabetical list with prosecution details available at IMDb)

Suggested Further Reading / References