Why Do People Believe in Conspiracy Theories?

I. Introduction

In a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center, nearly half of Americans said they believe in at least one conspiracy theory. Whether it’s the claim that the moon landing was staged, the belief that vaccines cause more harm than good, or the idea that shadowy elites control the global economy, conspiracy theories have carved out an indelible presence in our collective consciousness.

Conspiracy theories—narratives that attribute major events or situations to secretive, malevolent groups—aren’t new. From the paranoid whispers of medieval witch hunts to the modern labyrinths of QAnon forums, these beliefs are woven into the very fabric of human society. But why are they so alluring? Why do so many people, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, find comfort and conviction in them?

This blog will unpack the complex web of psychological, cognitive, and social factors that drive belief in conspiracy theories. We’ll explore how certain personality traits, thinking styles, and emotional needs fuel these beliefs, and how societal context—from economic crises to media polarization—can pour gasoline on the fire. Along the way, we’ll ground each concept with real-world examples, drawing a vivid map of how these shadowy stories take hold in hearts and minds.

II. Psychological and Motivational Roots

A. Personality Traits and Needs

At the heart of many conspiracy beliefs lie distinct personality traits and unmet psychological needs. Research consistently links traits such as paranoia, antagonism, insecurity, emotional volatility, and egocentrism with a greater tendency to endorse conspiratorial thinking. These individuals may not necessarily be irrational or delusional, but rather driven by a psychological need to impose order on chaos, or to assert control in situations where they feel powerless.

Believing in conspiracy theories can also satisfy motivational needs—like affirming one's self-worth or bolstering a fragile sense of identity. When people feel overlooked, disrespected, or anxious about their social standing, conspiracy theories offer them a sense of clarity and superiority. They get to be the ones “in the know,” the enlightened few in a world of sheep.

Real-World Example:

The QAnon movement exemplifies how certain psychological traits can manifest in widespread belief. Many adherents displayed deep distrust in institutions, coupled with a strong belief in their own moral clarity. Historically, the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion”, a fabricated anti-Semitic text from the early 20th century, preyed on public fears and personal insecurities, offering believers a scapegoat and a false sense of control amid societal upheaval.

B. Cognitive Needs and Emotional Security

When the world feels unpredictable, people instinctively look for narratives that restore order. Conspiracy theories—despite being factually flawed—can serve as emotional shock absorbers, providing psychological comfort in times of crisis. For many, especially during periods of trauma, grief, or instability, these theories become coping mechanisms.

They also fulfill a cognitive need for explanation. It’s easier to believe that a secret group orchestrated a tragedy than to accept that terrible things happen without reason. These theories turn randomness into design, suffering into strategy.

Real-World Example:

During the COVID-19 pandemic, uncertainty and fear led to a global explosion of conspiracy theories. From claims that the virus was engineered in a lab as a bioweapon to suspicions about microchips in vaccines, people clung to these narratives to make sense of a deeply disorienting reality. Believing there was a plan—however dark—offered more emotional security than facing the chaotic truth.

III. Cognitive Styles and Biases

A. Intuitive vs. Analytical Thinking

The way people think—how they process information and assess evidence—strongly influences their susceptibility to conspiracy theories. Those who rely primarily on intuitive thinking, or “gut feelings,” are more prone to believing conspiracies. Intuition is fast, automatic, and often emotionally charged. It doesn’t question evidence so much as it confirms what already feels true.

By contrast, analytical thinkers tend to be more skeptical of unsupported claims. They weigh evidence, consider alternative explanations, and require logical coherence before accepting a belief.

Real-World Example:

The flat Earth movement offers a stark illustration. Despite centuries of scientific evidence proving the Earth’s roundness, flat-earthers cling to their beliefs based on what “feels right”—like the perception that the ground feels flat underfoot. Analytical thinkers, meanwhile, consult astronomical data, satellite images, and physics to support their worldview.

B. Pattern Perception and Cognitive Biases

Conspiracy theorists often fall prey to cognitive distortions that influence how they interpret the world. These include:

-

Illusory pattern perception: seeing meaningful connections where none exist.

-

Jumping to conclusions: forming beliefs with minimal or ambiguous evidence.

-

Teleological thinking: attributing purpose or intent to random events.

These cognitive tendencies make it easier to link unrelated dots into an overarching narrative, especially in emotionally charged or ambiguous contexts.

Real-World Example:

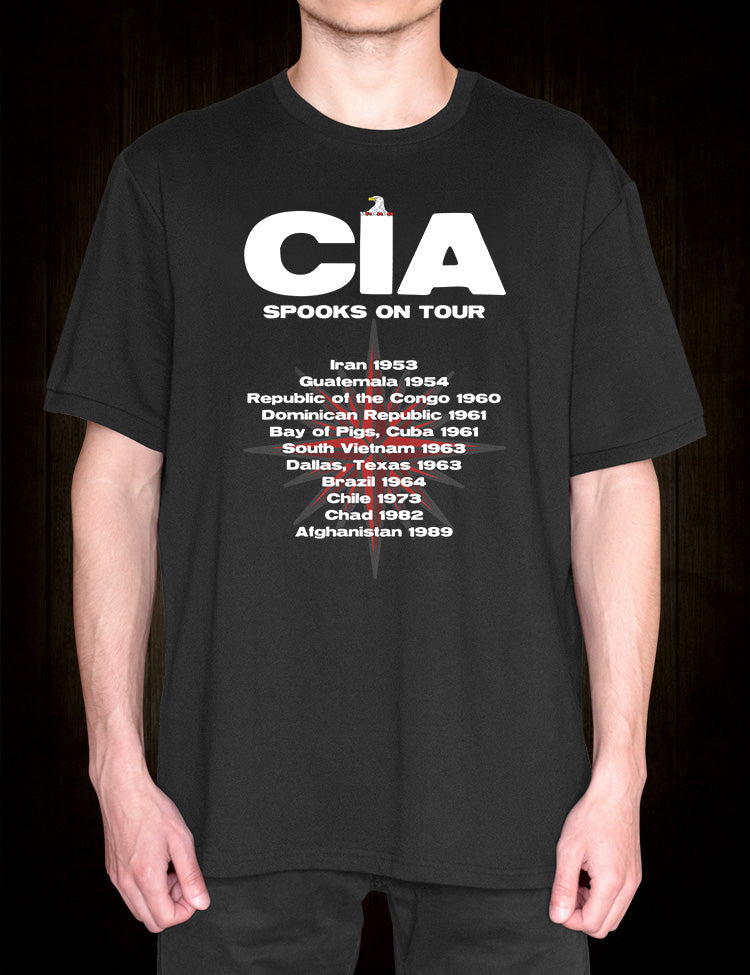

The JFK assassination remains fertile ground for such biases. From the “magic bullet” theory to alleged CIA involvement, believers construct elaborate narratives by interpreting coincidental details—like the timing of events or the positions of witnesses—as coordinated actions. Similarly, 9/11 “inside job” theories often rely on misinterpreted evidence and perceived patterns in governmental behavior and building collapses.

IV. Social and Emotional Factors

A. Feelings of Threat and Disenfranchisement

When individuals feel marginalized, powerless, or threatened, conspiracy theories become a way to externalize blame and restore a sense of agency. Social upheaval, rapid cultural change, and economic instability are all fertile ground for conspiratorial beliefs.

People experiencing chronic stress or who feel left behind by political or economic systems are especially vulnerable. Conspiracies offer a clear villain, a narrative that validates their frustrations and confirms that their suffering is no accident.

Real-World Example:

During economic downturns or job automation waves, beliefs in “elite cabals” or globalist plots have surged. Anti-immigrant conspiracy theories, for instance, often gain traction in areas where people fear cultural displacement or job competition, stoking xenophobia and group-based resentment.

B. Belonging and Group Superiority

Belief in conspiracy theories doesn’t just serve internal emotional needs—it also reinforces social bonds. Many people are drawn to conspiracy communities because they provide a sense of belonging, purpose, and shared identity. These groups often define themselves against the “mainstream,” creating a binary of the enlightened versus the deceived.

This belief structure also allows members to feel superior, morally and intellectually. “We know the truth. Everyone else is asleep.” It’s a psychologically powerful message, particularly for those who feel ignored or dismissed by wider society.

Real-World Example:

Communities like the anti-vaccine movement or 9/11 “truthers” often form tight-knit, self-reinforcing ecosystems online. Through hashtags, forums, and viral videos, they not only spread misinformation but also celebrate their insider status, portraying themselves as brave truth-tellers resisting a corrupt system.

V. Social Identity and Group Dynamics

Conspiracy theories often thrive in environments where group identity is deeply entrenched. For some, believing in a particular conspiracy is more than an individual choice—it’s a marker of belonging to a group that perceives itself as superior or marginalized. When a person’s identity is closely tied to a social group that feels threatened or oppressed, conspiratorial thinking can become a collective response to external pressures.

The allure of these theories is heightened by the desire for uniqueness—to feel special, to believe that “our group knows the truth others don’t.” This dynamic plays out across political, racial, and cultural lines, reinforcing in-group solidarity while casting suspicion on outsiders.

Real-World Example:

The belief in a “deep state” orchestrating political events taps into group dynamics of those who feel disenfranchised by mainstream institutions. Racially motivated conspiracies, like those surrounding immigration or voting fraud, exploit existing tensions and reinforce notions of cultural or political victimhood.

VI. General Conspiracy Mindset

What’s striking about conspiracy beliefs is how often they overlap and contradict each other. Research shows that a person who believes in one conspiracy theory is more likely to believe in others, even when those theories are logically incompatible. This reflects a general “conspiracy mindset”—a way of interpreting the world where hidden forces are presumed to be at work everywhere.

For these individuals, the content of a theory matters less than its underlying message: someone is controlling things from the shadows. The specifics shift, but the belief in hidden malice remains constant.

Real-World Example:

It’s not uncommon to encounter someone who believes both that COVID-19 was a hoax and that it was engineered as a bioweapon. These contradictions illustrate that conspiracy belief isn’t always about logical consistency—it’s about a deeper, pervasive mistrust of official narratives.

VII. Societal and Contextual Influences

A. Low Trust in Authorities

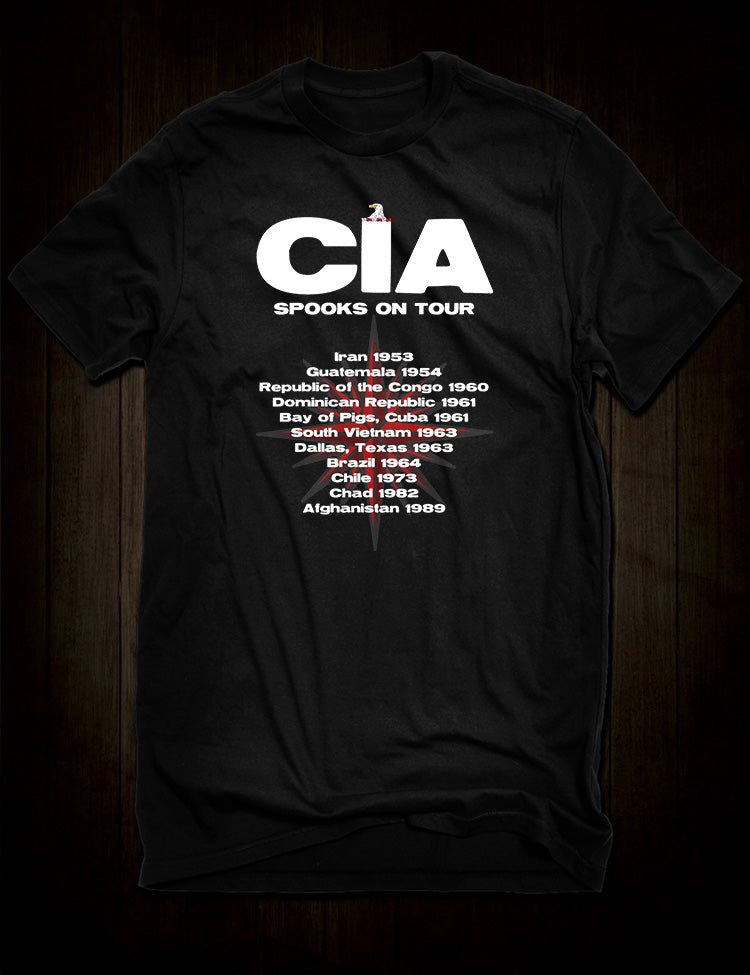

Public skepticism of governments, media, and scientific institutions creates fertile ground for conspiracy beliefs. When official narratives are distrusted, alternative explanations—no matter how outlandish—can seem more credible. Historical events like Watergate and revelations from Edward Snowden have only reinforced this skepticism, even when the conspiracies they uncover are far removed from the wilder theories.

Real-World Example:

Vaccine hesitancy often stems not from a misunderstanding of science but from a profound distrust in pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies, fueled by past scandals and perceived corruption.

B. Exposure to Misinformation and Polarization

In the digital age, the spread of misinformation has been supercharged by echo chambers, where people are exposed primarily to ideas that confirm their beliefs. Social media algorithms, designed to maximize engagement, often create filter bubbles that isolate users from contradictory evidence. This confirmation bias entrenches false narratives and makes it harder for accurate information to break through.

Real-World Example:

The explosive rise of Pizzagate—the false belief that a secret pedophile ring operated out of a Washington, D.C. pizzeria—or the denial of climate change illustrates how digital platforms amplify fringe ideas, turning isolated beliefs into viral movements.

VIII. Conclusion

The belief in conspiracy theories is shaped by a complex interplay of psychological, cognitive, and social forces. From deep-seated personality traits and cognitive biases to group dynamics and societal mistrust, these factors weave a tangled web that explains why conspiracies take root in so many minds.

Understanding these drivers isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s a crucial step toward improving public discourse and building resilience against misinformation. By recognizing the psychological needs and social contexts that fuel conspiracy beliefs, we can develop better educational tools, foster media literacy, and promote empathy and critical thinking.

In a world awash with information—and misinformation—the call is clear: stay curious, stay skeptical, and stay informed. Let’s question not just the narratives we’re told, but the reasons we believe them.