10 Infamous British Murder Trials That Changed History

Introduction

Murder trials are never just about the crime. They are stages upon which a society’s fears, values, and prejudices are laid bare. In the courtroom, questions of guilt and innocence intertwine with anxieties about class, gender, morality, and authority. Each verdict tells us not only about the accused but also about the world that judged them.

In Britain, certain trials have reverberated far beyond the dock. They have exposed weaknesses in policing, pushed forensic science into new territory, ignited furious debates about capital punishment, and reshaped the way the public thinks about justice. Some cases became morality plays in which the press cast villains and victims for mass consumption. Others forced the nation to confront uncomfortable truths: wrongful convictions, systemic biases, and the capacity for cruelty hidden in ordinary lives.

What follows is a journey through ten of the most infamous British murder trials of the twentieth century. From the transatlantic pursuit of Dr Crippen in 1910 to the chilling crimes of Dennis Nilsen and the Moors murderers decades later, each case shocked the public, dominated headlines, and left a mark on the legal and cultural fabric of the country. These stories are more than grisly episodes; they are milestones in the evolution of British justice.

In exploring them, we trace not only the crimes themselves but also the society that created, consumed, and ultimately changed because of them.

1) Hawley Harvey Crippen (1910)

Background: a mild man, a combustible marriage

Hawley Harvey Crippen didn’t look like a monster. Born in Coldwater, Michigan, in 1862, he trained in homeopathy, worked in patent medicines, and moved to London in the late 1890s to manage a branch for the flamboyant remedies magnate James Munyon. In 1894 he married Corrine “Cora” Turner—stage name Belle Elmore—a confident, social music-hall singer with a taste for attention and jewellery. The couple’s life in London was modest: by 1905 they were renting 39 Hilldrop Crescent, Holloway, taking in lodgers to make ends meet. Their worlds—and resentments—were misaligned: Cora chased the limelight and mixed with theatrical friends; Crippen counted pennies at a series of medical-adjacent jobs and began an affair with his young typist, Ethel Le Neve. By 1908, the affair was no secret in the quiet rooms of Hilldrop Crescent.

The marriage deteriorated sharply across 1909. Cora’s friends in the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild noticed rows and bruising gossip; Crippen, meanwhile, was quietly ordering hyoscine hydrobromide (scopolamine)—a powerful anticholinergic sedative—five grains from a New Oxford Street chemist on 15 January 1910. Two weeks later, on the night of 31 January, the Crippens hosted friends at Hilldrop, played cards late, and said their goodnights. No one outside that house ever saw Cora again.

Disappearance, suspicion—and a cellar discovery

Crippen’s explanations for Cora’s absence changed with practised, almost bureaucratic calm. First he said she’d fled to America with a lover; then, astonishingly, that she had died and been cremated in California. Le Neve—now living openly at Hilldrop and wearing Cora’s clothes and jewellery—only sharpened the sense that something was amiss. Friends, among them the performer Lil Hawthorne and her husband John Nash, pressed Superintendent Frank Froest at Scotland Yard to act. Chief Inspector Walter Dew paid an initial visit; the house was searched and nothing found. Under questioning, Crippen admitted he’d lied about Cora’s death—claiming embarrassment rather than murder—and Dew, momentarily satisfied, left. But Crippen and Le Neve panicked and bolted for the Continent. Their flight triggered a more thorough examination of 39 Hilldrop Crescent. On a later search, detectives lifted the bricks in the coal cellar and uncovered a headless, limbless torso—a “mass of flesh”—wrapped with pajama material and other fragments, including bleached hair and curl papers.

Home Office analyst William Willcox tested the remains and reported traces of hyoscine hydrobromide—a chemical line straight back to Crippen’s January order. Meanwhile, pathologist Bernard Spilsbury, not yet the celebrity expert he would become, examined a section of abdominal skin and told the court he saw a surgical scar that matched Cora’s medical history. Police also seized on the pajama fragment, whose “Jones Bros.” maker’s label could be dated to post-1908—important because the defence would later hint the remains pre-dated the Crippens’ tenancy. The label suggested otherwise.

The modern manhunt: arrested by wireless

Crippen and Le Neve, travelling as “Mr John (or John Philo) Robinson” and his teenage “son,” slipped to Antwerp and boarded the SS Montrose, bound for Quebec, on 20 July 1910. Their second-class cabin should have kept them anonymous—except that the Montrose had a sharp-eyed captain, Henry George Kendall, and a Marconi wireless. Kendall believed he recognised the pair; his radio operator, Lawrence Ernest Hughes, tapped an urgent message to Britain: suspicious fugitives aboard, man with shaved moustache, “boy” really a woman. The press—and the public—followed the chase in real time. Walter Dew commandeered the faster White Star liner Laurentic, raced the Atlantic, and reached the St Lawrence ahead of the Montrose. On 31 July, posing as a harbour pilot, Dew stepped aboard and delivered the line that pivoted the case from sensation to history: “Good morning, Dr Crippen. Do you know me?” Crippen reportedly replied, “Thank God it’s over.” He and Le Neve were arrested without drama. It was the first high-profile arrest enabled by wireless telegraphy, a new age of policing performed in public.

The Old Bailey, October 1910: anatomy of a conviction

Crippen was tried at the Old Bailey before the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Alverstone, beginning 18 October 1910; Ethel Le Neve would be tried later as an accessory. The prosecution team featured the formidable Richard D. Muir, renowned for meticulous cross-examination; the defence was led by Alfred Tobin KC. Proceedings lasted four days—swift by modern standards.

The Crown’s case knitted together four strands:

-

The remains: Spilsbury’s scar testimony suggested the torso was Cora’s; the defence countered that the “scar” showed hair follicles, which true scar tissue shouldn’t, and was merely folded skin. Spilsbury held firm, noting sebaceous structures at the edges but not in the centre.

-

The poison: Willcox’s chemical analysis reported hyoscine in the flesh—consistent with a sedative or fatal dose. The Crown pointed to Crippen’s hyoscine purchase in January as both capability and intent. WikipediaRSC Books

-

The pajamas: A Jones Bros. label on a pajama fragment wrapped among the remains could be dated no earlier than 1908. That timing, the prosecution argued, put the burial within the Crippens’ occupancy and long after any previous tenant could be responsible. The matching pajama bottoms were reportedly found in Crippen’s bedroom; the top was missing.

-

Conduct and flight: Crippen’s changing stories, Le Neve wearing Cora’s outfits, and the hurried flight under aliases sketched a consciousness of guilt rather than embarrassment. Wireless-tracked pursuit gave the Crown the drama—and the logic—of a suspect running from his own lies.

The defence’s alternative narrative tried to prise each seam apart. Tobin leaned on reasonable doubt: Cora, he said, left with her lover Bruce Miller; the torso could have been buried before the Crippens moved in (hence the wrangle over the pajamas); and even Spilsbury admitted that with so much of the skeleton missing, absolute identification was impossible. Above all, the defence cast the Crown’s case as a chain of inferences anchored to an unidentified body. Crippen himself kept his answers cool and sparing on the stand; tellingly, he refused to let Le Neve testify for him—apparently to shield her reputation.

Muir’s cross-examination, though, was punishing. He picked at timings, at the implausibility of Cora’s supposed American cremation, and at the hyoscine trail. The jury needed less than half an hour—27 minutes—to convict. Crippen was sentenced to death and hanged at Pentonville on 23 November 1910. Le Neve was tried separately and acquitted of being an accessory. The case was over, neatly wrapped. Or so it seemed.

Why Crippen’s case changed history

Two legacies are indisputable. First, policing: the Crippen chase marked a new, networked era of manhunts, with the public following along in newspapers as wireless messages leapt ship-to-shore. Capt. Kendall’s decision to radio suspicions from the SS Montrose and Dew’s race aboard the SS Laurentic reshaped expectations of how swiftly fugitives could be tracked—across oceans and in near-real time.

Second, forensics: the trial showcased toxicology and pathology in the absence of a full body—hyoscine in soft tissue, a putative scar on preserved skin, and manufacturing data wrung from a pajama label. Those elements made the case a touchstone in debates about what counts as identification and how far circumstantial science can carry a prosecution when the bones—and the face—are missing.

The controversy that won’t die

From the very beginning, critics fretted about the identification of the remains. In the 2000s, a team led by David Foran at Michigan State University reported mitochondrial DNA from preserved slides did not match Cora’s maternal relatives—and that a Y-chromosome signal suggested the tissue was male, not female. If true, the torso couldn’t be Cora’s; the case for murder, at least as charged, would collapse into something darker: a misidentification at the heart of a hanging. Their study appeared in the Journal of Forensic Sciences in 2010/2011 and was widely reported.

But the pushback has been fierce. Methodology and contamination concerns linger over century-old slides. In 2025, geneticist Prof. Turi King publicly criticised the original DNA work as “not up to standard”, urging a re-examination with modern techniques if samples can be reliably verified. Meanwhile, historians and journalists continue to point out the other evidence—hyoscine in the flesh, the pajama label, the couple’s flight—that still looks compelling, even if the identification is argued. In short: the science is unsettled; the legend endures.

Bottom line

Crippen’s story is a prism. Tilt it one way and you get a cautionary tale about jealousy, poison, and a new technology of pursuit that left nowhere to hide. Tilt it the other and you get a century-long argument about forensic certainty—scar vs. fold, label vs. timeline, DNA vs. degradation. Either way, the case changed British criminal history: it professionalised public expectations of police speed, dramatised the power and the perils of expert testimony, and made the Old Bailey grapple—loudly, and in print—with how far you can go without a face or a name on the slab. And that, more than the moustaches and melodrama, is why Crippen’s shadow still falls across the dock.

2) Edith Thompson & Frederick Bywaters (1922)

Background: a suburban marriage on the rocks

Edith Jessie Thompson was born in 1893 in Dalston, East London, the eldest of five children. Bright, imaginative, and socially ambitious, she secured a respectable job as a secretary at a wholesale millinery firm, where her quick mind and flair for fashion impressed employers. In 1916, during the thick of the First World War, she married Percy Thompson, a shipping clerk. On paper the Thompsons were a model middle-class couple: they bought a neat house at 41 Kensington Gardens, Ilford, rode in to work together each day, and presented a picture of stability to their families. Beneath the surface, however, the marriage was brittle. Edith found Percy dour, controlling, and emotionally distant; Percy bristled at her sharp tongue and independent streak.

Into this claustrophobic domestic life stepped Frederick Bywaters, a 20-year-old shipping clerk and former lodger at the Thompsons’ house. Handsome, athletic, and six years younger than Edith, Fred represented everything her marriage lacked—romance, adventure, vitality. By 1921, the two had embarked on a passionate affair. Edith’s infatuation was captured in a torrent of letters she wrote to Fred: hundreds of pages filled with longing, resentment toward Percy, and fantasies—sometimes violent—about escaping her marriage. In several letters she mused about poisoning her husband or wishing him dead. Whether these were genuine intentions, melodramatic flourishes, or a lover’s fantasy has been the central question of her legacy.

The killing on Ilford Lane

On the night of 3 October 1922, Edith and Percy attended a play at the Criterion Theatre in London’s West End. As they walked home from Ilford station along Ilford Lane, Fred Bywaters sprang from the shadows and attacked Percy with a knife, stabbing him multiple times. Percy died almost instantly. Edith, hysterical, was found at the scene screaming for help. Police quickly linked Bywaters to the killing; he was arrested within hours. The more shocking twist came when detectives uncovered Edith’s cache of love letters, brimming with murderous talk and dark fantasies.

The trial at the Old Bailey

The joint trial of Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters opened at the Old Bailey on 6 December 1922 before Mr Justice Shearman. The press descended in force. For the prosecution, the case was clear: Bywaters had carried out the physical act, but Edith’s letters showed her to be the intellectual instigator—the woman who had poisoned his mind with repeated suggestions that her husband should die. The Crown argued that she was not only complicit but the true author of Percy’s fate.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Edith’s letters were read at length, with phrases about poisoning, breaking bottles in Percy’s food, or willing him dead given maximum emphasis.

-

The emotional intensity of the correspondence was portrayed as manipulative and unbalanced, painting Edith as a femme fatale who seduced a younger man into murder.

-

Bywaters’ act, they argued, was not spontaneous but the culmination of Edith’s sustained encouragement.

The Defence’s case:

-

Edith’s counsel, Henry Curtis-Bennett KC, argued that the letters were romantic fantasy, not evidence of a conspiracy. Edith, he said, was a woman trapped in an unhappy marriage, prone to imaginative exaggeration.

-

There was no concrete proof she had taken any physical steps to harm Percy, nor that she knew Fred would attack him on Ilford Lane.

-

Bywaters himself testified that Edith had never asked him to kill Percy and that he had acted out of passion, alone. His insistence on her innocence was striking—but ultimately dismissed.

Media frenzy and gendered scrutiny

The trial became a sensation. Newspapers splashed lurid extracts of Edith’s letters, often stripped of context, casting her as a sexually voracious and manipulative adulteress. The fact that she had an affair at all was scandal enough in 1920s Britain; combined with Percy’s murder, it created an irresistible moral drama. Edith’s appearance in court—fashionable, expressive, at times visibly distressed—was contrasted with the stoicism expected of women in such circumstances. Critics argued she was tried not only for murder but for being a woman who transgressed the bounds of respectability.

Bywaters, in contrast, was framed as a reckless but romantic youth, tragically ensnared by an older woman’s influence. The gender dynamics were stark: Edith’s sexuality and imagination were weaponised against her, while Fred’s violence was cast in the shadow of her supposed manipulation.

Verdict and execution

On 11 December 1922, after little more than two hours of deliberation, the jury returned guilty verdicts against both defendants. Despite Bywaters’ repeated declarations that Edith had no part in planning the murder, both were sentenced to death. Appeals for clemency flooded in for Edith—signed by writers, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens who believed her guilty of adultery but not of murder. The Home Secretary, Edward Shortt, refused to intervene.

On the morning of 9 January 1923, Edith Thompson was hanged at Holloway Prison. Eyewitnesses reported that she collapsed in terror and had to be carried to the scaffold—details that only fuelled the sense of injustice surrounding her death. At the same hour, Fred Bywaters was executed at Pentonville. He died insisting Edith had known nothing of his intentions.

Historical impact

The Thompson-Bywaters case reverberated through British culture for decades:

-

Capital punishment debate: Edith’s execution became one of the most contested in British history, often cited as an example of how the death penalty could be applied unjustly, particularly against women. Campaigners for abolition repeatedly referenced her case.

-

Gender and morality: The trial laid bare how female sexuality was policed in the courtroom. Edith was punished as much for her adultery and unrestrained imagination as for any provable complicity in murder. Scholars have argued she was “judged for her letters, not her deeds.”

-

Cultural legacy: The case inspired plays, novels, and films—including the 2001 film Another Life and various retellings that cast Edith as either villainess or tragic heroine. The letters themselves remain haunting documents, oscillating between melodrama and yearning.

-

Legal lessons: While the Crown could argue Edith had “incited” the crime through her words, her conviction exposed the dangers of conflating fantasy with conspiracy. Modern courts have since been far more cautious about treating private correspondence as direct evidence of murderous intent.

Bottom line

The trial of Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters was more than a sordid domestic tragedy; it was a cultural reckoning. Edith’s fate revealed how a woman’s passion could be recast as pathology, how letters could outweigh facts, and how the machinery of justice could bend beneath the weight of social prejudice. Whether guilty of murder in law or guilty only of desiring freedom, Edith Thompson became an enduring symbol of injustice in British criminal history—proof that trials tell us as much about the society that conducts them as about the crime itself.

3) Neville Heath (1946)

Background: charm, trauma, and deceit

Neville George Clevely Heath was born in Ilford, Essex, in 1917, the son of a respectable lower-middle-class family. He grew up intelligent, articulate, and, by many accounts, attractive and charismatic. Heath’s childhood was not outwardly remarkable, but even in adolescence he developed a tendency toward deceit and manipulation. After leaving school, he took jobs in banking and later drifted into the RAF during the Second World War.

Heath’s military record was chequered. He was commissioned as a pilot officer in 1939, but discipline proved elusive. He was court-martialled for going absent without leave, embezzlement, and writing fraudulent cheques. His RAF career ended in disgrace. When he later enlisted in the South African Air Force, the pattern repeated—he was expelled for theft. These failures did not dull his surface charm. In civilian life he continued to reinvent himself with a string of aliases, including “Lord Dudley” and “Group Captain Armstrong.”

Behind this charm lay troubling patterns: a history of sadistic sexual tendencies, a need for control, and a capacity for extreme violence that would manifest horrifically in 1946.

The first murder: Margery Gardner

On the evening of 20 June 1946, Heath met Margery Gardner, a 32-year-old divorcee, at the Panama Club in Kensington. Margery was known in post-war London’s nightlife scene—vivacious, independent, and looking to enjoy herself after years of wartime austerity. Heath, presenting himself as well-spoken and affluent, swept her into his orbit.

The two spent the night together at a flat in Notting Hill. By morning, Margery was dead. Her body was discovered with multiple injuries: she had been gagged, whipped, and strangled with a silk stocking. Marks on her wrists and ankles indicated she had been bound. Police determined the level of violence far exceeded anything consensual. The brutality suggested a sadistic ritual: Margery had been degraded and tortured before death.

Heath, now wanted for murder, did not linger. He moved swiftly to Bournemouth on the south coast, under another alias.

The second murder: Doreen Marshall

Barely three weeks later, Heath struck again. On 4 July 1946, he encountered Doreen Margaret Marshall, a 21-year-old WREN (Women’s Royal Naval Service member), in the lounge of the Tollard Royal Hotel in Bournemouth. She was polite, fresh-faced, and newly returned from service. Heath played the role of gallant ex-officer, charming her over dinner.

When Doreen failed to return to the hotel the next day, staff became concerned. Heath explained that she had left suddenly, but suspicions mounted. On 8 July, police discovered her mutilated body in a secluded area of Bournemouth’s Branksome Dene Chine. The injuries were even more appalling than those inflicted on Margery Gardner: Doreen had been savagely beaten, her throat cut, and subjected to prolonged torture. Pathologists later described the injuries as the worst they had seen outside of wartime atrocities.

Heath, remarkably, presented himself at Bournemouth police station on 5 July, ostensibly to “assist” with inquiries. He was calm, well-dressed, and cooperative. But when inconsistencies in his story emerged and his identity as the wanted man in the Gardner case was revealed, he was arrested.

The trial at the Old Bailey

Heath’s trial began at the Old Bailey on 24 September 1946, presided over by Mr Justice Gorman. Public interest was feverish. Britain was only just emerging from the war; newspapers sold the story of a “handsome ex-RAF officer turned sadistic killer,” a narrative that horrified and fascinated readers in equal measure.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Led by Hartley Shawcross KC (who had also served as chief prosecutor at Nuremberg), the Crown argued that Heath’s killings were marked by deliberate sadism.

-

Medical evidence showed the extent of torture inflicted on both women, demonstrating intent and premeditation.

-

Witnesses from the hotel and the Panama Club placed Heath with both victims in their final hours.

-

Forensic evidence—bloodstains, items belonging to the women—linked him directly to the scenes.

The Defence’s case:

-

Heath’s counsel, J. D. Casswell KC, attempted an insanity defence, suggesting his client was suffering from a form of psychopathy that impaired his control.

-

They drew on psychiatric evaluations that indicated Heath had abnormal impulses, a lack of empathy, and pathological lying.

-

However, the threshold for the insanity plea (under the M’Naghten Rules) required proof that the accused did not know the nature of his acts or that they were wrong. The jury was not convinced.

Heath himself did not help his case. Though initially calm and composed, he showed flashes of arrogance and detachment that alienated the jury. He admitted to being present during the attacks but attempted to portray them as acts of consensual sexual play gone wrong. Given the sheer brutality of the injuries, this claim rang hollow.

Verdict and execution

The jury took only an hour to return a verdict of guilty. Mr Justice Gorman donned the black cap and pronounced sentence of death. Neville Heath was executed by hanging at Pentonville Prison on 16 October 1946, only three weeks after his trial. He was 29 years old. Reports suggested he remained calm in his final days, receiving Catholic rites before walking steadily to the scaffold.

Historical impact

The Heath case resonated for several reasons:

-

The “gentleman killer” archetype: Heath embodied a post-war fear that evil could lurk behind a polished exterior. He was no lurking stranger in a dark alley but a well-dressed, educated, apparently respectable man. The notion that brutality could wear a charming face unsettled the public deeply.

-

Sadism and sexuality: The crimes forced Britain to confront uncomfortable links between sexuality and violence. The brutality inflicted on Margery and Doreen shocked a society that still preferred to keep such matters unspoken. The press, while sensationalising, also hinted at wider anxieties about “perversion” and moral decline in the aftermath of war.

-

Insanity defence scrutiny: The trial highlighted the limitations of the M’Naghten Rules, set in the 19th century, in dealing with complex psychiatric conditions like psychopathy. Heath was clearly abnormal, but not legally “insane.” His case became part of the ongoing debate about how the law should treat mental disorder in violent crime.

-

Post-war social mood: Britain in 1946 was still reeling from trauma. Millions had endured violence, death, and dislocation. Against that backdrop, Heath’s murders felt like a grotesque continuation of wartime horror in peacetime streets. The savagery inflicted on young women tapped into national anxieties about security, morality, and the fragility of order.

Bottom line

Neville Heath’s story is not merely one of sadistic violence; it is a parable about masks. He was the charming ex-officer who concealed cruelty behind manners, the “gentleman” who revealed the abyss when doors were shut. His trial forced Britain to acknowledge that evil did not always announce itself with madness or poverty—it could arrive in tailored suits and with polished speech. In the aftermath, Heath entered the canon of Britain’s most notorious killers, his case remembered both for its extraordinary brutality and for the way it stripped the veneer from post-war respectability.

4) John George Haigh – “The Acid Bath Murderer” (1949)

Background: fraudster with a taste for murder

John George Haigh was born in 1909 in Stamford, Lincolnshire, into a strict Plymouth Brethren household. His parents believed in rigid morality and isolation from the “corrupt” outside world. Haigh later described his upbringing as austere and loveless: a father who imposed severe religious discipline and a mother who believed sin manifested physically in marks upon the body. These early experiences, Haigh later claimed, left him repressed, lonely, and prone to fantasy.

Despite his sheltered upbringing, Haigh excelled academically and musically—he was a capable pianist and organist. But his adult life quickly spiralled into deceit. In the 1930s he worked as a chauffeur and salesman, dabbling in petty frauds and forging documents. His first conviction in 1934, for forging vehicle documents, earned him a prison sentence. While incarcerated, Haigh absorbed a key lesson that would shape his future crimes: fraud left witnesses, but murder erased them.

When released, he drifted between odd jobs, scams, and short prison spells. He reinvented himself repeatedly: as an inventor, an entrepreneur, and a charming man-about-town. Beneath the surface, however, he was developing a method of killing that would make him infamous: dissolving bodies in sulphuric acid.

The first known murders

Haigh’s killings began during the Second World War, though his first attempts at disposing of bodies were crude and incomplete. His first confirmed victims were William McSwan, a wealthy playboy he befriended in 1944, and McSwan’s parents, Donald and Amy. Haigh lured William to a basement workshop in Gloucester Road, bludgeoned him, and placed the body in a drum filled with sulphuric acid. Within days, the flesh had liquefied. Haigh tipped the residue down a manhole.

He repeated the process with William’s elderly parents after convincing them their son had gone into hiding to avoid military service. In reality, he murdered them in the same workshop and dissolved their remains. Haigh took control of the McSwans’ property and finances, forging documents and pocketing rents. For the first time, murder and fraud had fused in a way that satisfied both his greed and his sense of omnipotence.

The Hendersons and beyond

Flush with stolen wealth, Haigh moved on to his next victims: Dr Archibald and Rose Henderson, an affluent couple he met while posing as an engineer. He gained their trust by pretending to share their interest in classical music and by ingratiating himself into their social circle. In 1948, he lured them to his workshop, killed them with a revolver, and subjected their bodies to the acid treatment. Again, he forged documents to gain access to their property and possessions.

But Haigh’s greed outpaced his skill at concealment. He began living lavishly—gambling, buying cars, and dressing expensively. His lifestyle raised questions. When he murdered his final victim, Mrs Olive Durand-Deacon, a wealthy widow who had discussed investing in a fictitious invention of his, he finally made a mistake that drew police attention.

The arrest and investigation

On 18 February 1949, Mrs Durand-Deacon vanished after visiting Haigh’s workshop at Crawley. When she did not return to her Kensington hotel, her friends raised the alarm. Police traced her to Haigh, who appeared nervous but cooperative. A search of the workshop revealed incriminating evidence: a rubber apron, gas masks, industrial drums, and a revolver. Most damningly, forensic scientist Dr Keith Simpson examined sludge and residue from the acid drums. He identified three human gallstones and a fragment of denture, matching the dental work of Mrs Durand-Deacon.

Haigh confessed almost immediately, but with a peculiar strategy: he admitted to multiple murders—McSwan and his parents, the Hendersons, and Mrs Durand-Deacon—but insisted he was insane. He told police he had recurring dreams of blood, vampires, and compulsion. “The urge to kill,” he claimed, “was overwhelming.”

The trial at Lewes Assizes

Haigh was charged with the murder of Mrs Durand-Deacon only, the Crown arguing that one clear case was enough for a capital conviction. The trial opened at Lewes Assizes on 18 July 1949, before Mr Justice Humphreys.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Led by Hartley Shawcross KC (who had prosecuted Neville Heath just three years earlier), the Crown focused on the overwhelming forensic evidence: the dentures, gallstones, and chemical residue that proved Mrs Durand-Deacon’s body had been destroyed in Haigh’s workshop.

-

Witnesses testified to Haigh’s financial motives, detailing how he had forged signatures, transferred assets, and used his victims’ possessions.

-

The evidence of prior murders, though not formally charged, was introduced to show pattern and intent.

The Defence’s case:

-

Haigh’s counsel argued he was legally insane, driven by vampiric delusions and unable to control his impulses. Psychiatric experts, however, disagreed: while Haigh displayed narcissism and psychopathic traits, he clearly understood his actions and their consequences.

-

Haigh’s confession itself undermined the plea: he admitted he had considered the acid would destroy the bodies and prevent detection—demonstrating planning and awareness of criminality.

Haigh, impeccably dressed and calm, behaved with an eerie detachment in court. At times he appeared amused by the proceedings, at others he described his killings with chilling matter-of-factness. The press dubbed him the “Acid Bath Murderer,” a label that fused scientific horror with tabloid melodrama.

Verdict and execution

The jury took little time—just minutes—to reject the insanity defence. Haigh was found guilty of murder on 19 July 1949. Sentenced to death, he was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 10 August 1949 by executioner Albert Pierrepoint.

Witnesses reported that Haigh remained composed to the end. His last meal was a traditional breakfast of eggs, bacon, and toast; he declined the customary glass of brandy. As he mounted the scaffold, he offered no final words.

Historical impact

The Haigh case left several enduring marks on British criminal history:

-

Forensic triumph: The discovery of dentures and gallstones in acid sludge by Dr Keith Simpson became a textbook example of forensic perseverance. It demonstrated that even the most extreme attempts to obliterate a body could fail under scientific scrutiny.

-

Insanity defence scrutiny: Haigh’s failure to secure an insanity verdict reinforced the difficulty of using psychiatric pleas under the strict M’Naghten Rules. His vampiric fantasies may have been colourful, but they did not absolve him of responsibility.

-

Public horror: The idea of dissolving victims in acid captivated and horrified the public imagination. Haigh became a symbol of modern, “scientific” murder, contrasting with older images of domestic poisoning or crimes of passion. His killings seemed industrial, cold, and clinical.

-

Media myth-making: Haigh’s calm demeanour, sharp suits, and articulate testimony contrasted grotesquely with the brutality of his crimes, feeding the trope of the “gentleman killer.” Newspapers revelled in the paradox, ensuring his place in British criminal folklore.

-

Cultural resonance: The “acid bath” imagery inspired crime writers, filmmakers, and sensationalist reporting for decades. Haigh’s case is still referenced in criminology courses and true crime literature as an example of forensic detection triumphing over a calculated method of body disposal.

Bottom line

John George Haigh was not the first fraudster to kill his way to financial gain, but he perfected a method that shocked Britain with its cold ingenuity. By dissolving his victims in acid, he thought he had found the perfect crime. Instead, he demonstrated that science could be as powerful in revealing truth as in concealing it. Haigh’s trial, with its blend of horror, forensic drama, and courtroom spectacle, cemented his place among Britain’s most notorious killers and underscored how technology—whether in the hands of a murderer or a pathologist—can change the landscape of crime and justice.

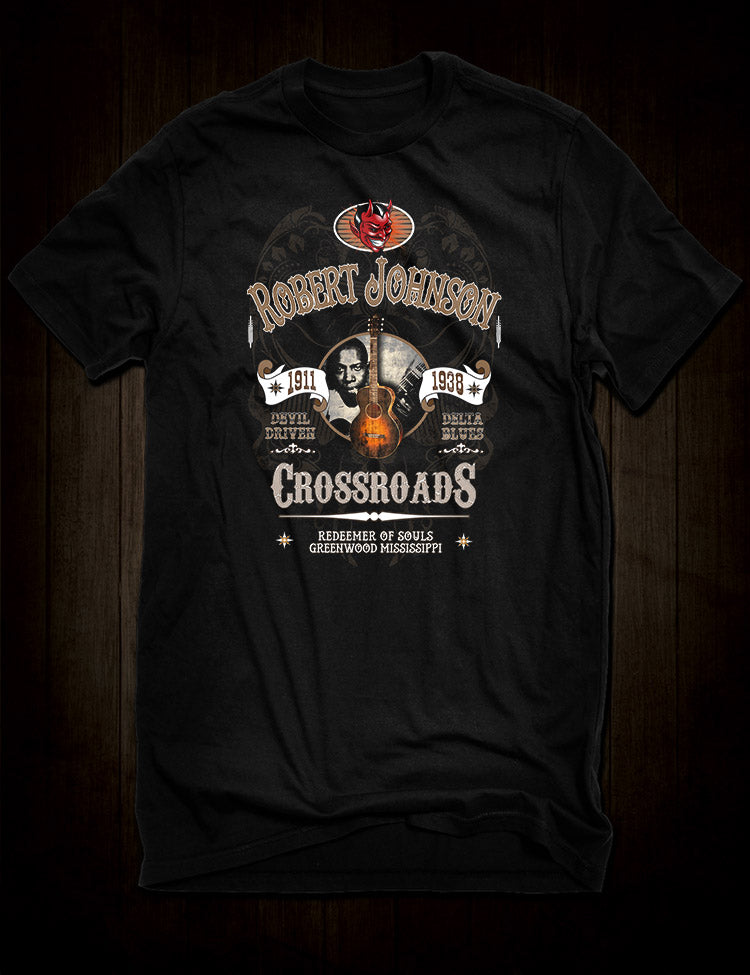

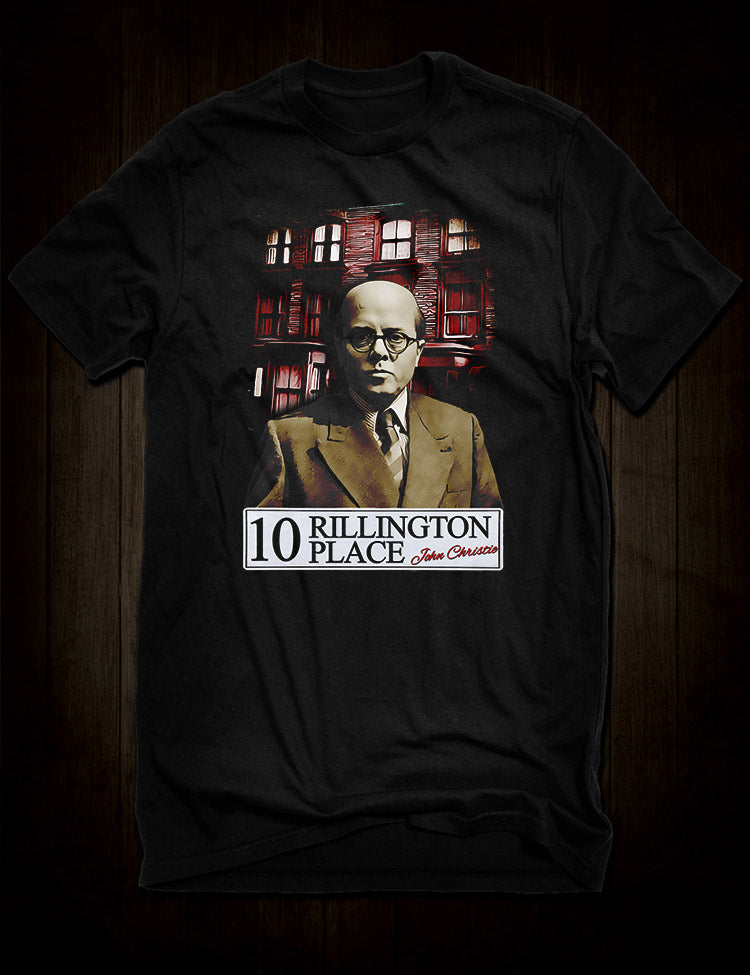

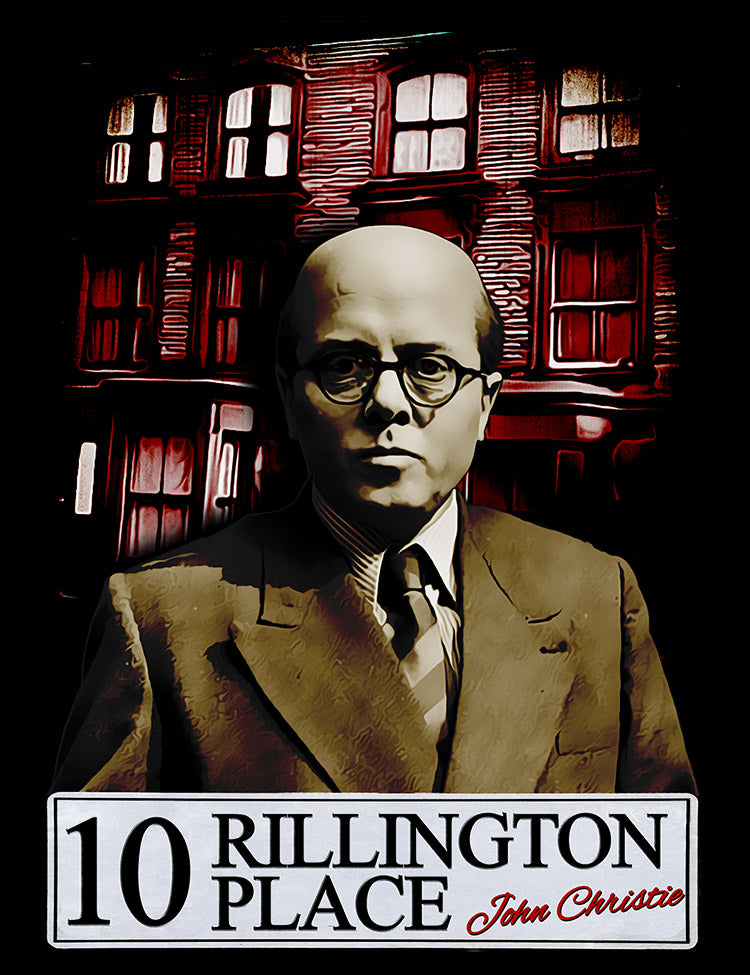

5) Timothy Evans & 10 Rillington Place (1950)

Background: an ordinary man with limited means

Timothy John Evans was born in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales, in 1924. His early life was marked by hardship. He grew up without his father, struggled at school, and left largely illiterate. By his teens he had developed a reputation as impressionable, sometimes boastful, and prone to simple-minded exaggerations. After the war, Evans moved to London in search of work. He married Beryl Thorley in 1947, and in April 1948 their daughter Geraldine was born.

The Evanses lived in poverty. By 1949 they were tenants at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, a drab terrace house in a seedy, bomb-damaged neighbourhood. Their landlord and downstairs neighbour was John Reginald Halliday Christie, a seemingly mild-mannered ex-police constable who offered Evans occasional help. The marriage was turbulent—rows over money and Beryl’s frustration at their circumstances were common. Into this fragile situation, Christie insinuated himself as a confidant and, ultimately, a predator.

The tragedy of November 1949

In November 1949, tensions came to a head. Evans returned home one day to find both Beryl and their infant daughter missing. Distressed, he gave contradictory accounts to neighbours and family. Eventually he told police that Beryl had died during a botched abortion performed by Christie, and that Christie had promised to dispose of the body. Later, Evans changed his story again, claiming he himself had accidentally killed Beryl by giving her something to “ease her troubles,” then panicked.

On 2 December 1949, police searching 10 Rillington Place discovered Beryl’s body in a washhouse at the back of the property. A second, grimmer discovery followed: baby Geraldine, strangled, hidden in the flat. Evans was arrested immediately.

The investigation and Evans’ confessions

The police investigation into the case was riddled with shortcomings. Evans gave multiple conflicting statements, some implicating Christie, others taking responsibility himself. At times he claimed Christie had performed an abortion on Beryl; at others he admitted to quarrelling and killing her in a rage. Detectives, eager for a quick solution, seized on the version in which Evans confessed. His poor literacy and limited understanding of events made him vulnerable to pressure.

Christie, meanwhile, appeared calm and cooperative. He supported the narrative that Evans was guilty, downplaying his own involvement. Police never fully considered the possibility that Christie, a man with a known criminal record including sexual assault, could be lying.

The trial at the Old Bailey

Evans was tried at the Old Bailey in January 1950, before Mr Justice Lewis. The charge was not Beryl’s murder but that of baby Geraldine, because the prosecution believed this case was most straightforward and least vulnerable to conflicting evidence.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Evans had admitted to killing Geraldine in one of his statements.

-

He had motive: marital strife, frustration, and desire to be free of responsibility.

-

The physical evidence, while circumstantial, was presented as consistent with his guilt.

The Defence’s case:

-

Evans’ lawyer argued his confessions were unreliable, extracted under pressure from a man of limited intelligence.

-

Christie should have been a prime suspect, given his presence in the house and his background.

-

There was no direct evidence linking Evans to Geraldine’s murder.

Despite this, the jury found Evans guilty after just 40 minutes of deliberation. He was sentenced to death.

Execution and immediate aftermath

On 9 March 1950, Timothy Evans was hanged at Pentonville Prison by Albert Pierrepoint. He was 25 years old. Outside the prison, a small crowd gathered—some convinced of his guilt, others uneasy. Evans maintained his innocence until the end.

At the time, the case appeared closed. Christie remained a respectable figure in the house, a quiet widower who had even testified against Evans. But three years later, events would expose the horrifying truth: Evans had been innocent.

Why the case mattered

The Evans trial was a turning point in British justice:

-

Wrongful conviction: Evans’ hanging became one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in British history. His confessions, contradictory and confused, should never have been the foundation of a capital conviction.

-

Death penalty debate: Evans’ fate became a rallying cry for campaigners against capital punishment. If the state could execute an innocent man, abolitionists argued, no one could be safe.

-

Police failings: The investigation’s incompetence—failure to scrutinise Christie, reliance on dubious statements, and tunnel vision—highlighted deep flaws in policing.

-

Public trust: When Christie was later unmasked as a serial killer, outrage erupted. How had police not seen what was under their noses? Evans’ execution became symbolic of a justice system more concerned with expedience than truth.

Bottom line

The tragedy of Timothy Evans was not simply that an innocent man was executed—it was that the real killer lived beneath him, offering help while committing murder. Evans’ trial revealed how vulnerable individuals could be coerced into false confessions, and how blind faith in authority could lead to catastrophic errors. The case is remembered as one of the most powerful arguments for ending the death penalty in Britain, and it remains a chilling reminder of how fragile justice can be when built on shaky ground.

6) John Reginald Halliday Christie (1953)

Background: a predator hiding in plain sight

Born in Halifax, Yorkshire, in 1899, John Reginald Halliday Christie grew up in a troubled household. His father was stern and his mother overprotective. By adolescence he exhibited disturbing tendencies: an obsession with prostitutes, a fascination with control, and difficulties in forming normal relationships. During the First World War, Christie served as a signalman and later claimed a mustard gas injury left him with permanent weakness of voice, though this was likely exaggerated.

Christie married Ethel Simpson in 1920. The marriage was rocky—he was domineering and unfaithful, and for a period they lived apart. Christie’s early criminal record included theft and violent assault, including an attack on a prostitute. Yet he projected a façade of respectability: polite, mild-mannered, and employed steadily in clerical work. In 1938, the Christies moved into the ground-floor flat at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, the same address that would later become synonymous with horror.

Christie’s pattern of murder

Christie’s killings spanned over a decade. His method was distinctive: he would lure women, often vulnerable or desperate, with promises of medical help—particularly abortions, which were illegal at the time. He would then incapacitate them with domestic gas (carbon monoxide), often delivered through a tube and mask, and sexually assault them while they were unconscious or dying.

His first known victim was Ruth Fuerst, a prostitute he killed in 1943 and buried in the garden. In 1944 he murdered Muriel Eady, gassing her under the pretense of a medical experiment, then assaulting and strangling her. Both bodies lay hidden near the house for years.

In 1949 came the Evans tragedy. Christie offered to help Beryl Evans with an abortion. Instead, he killed her and later strangled baby Geraldine. When police investigated, Christie manipulated events to implicate Timothy Evans, who was ultimately executed. Christie’s testimony at trial bolstered the false narrative.

After Evans’ death, Christie continued killing. In December 1952 he strangled his own wife, Ethel, and buried her under the floorboards. Between January and March 1953 he murdered three more women—Rita Nelson, Kathleen Maloney, and Hectorina MacLennan—luring them with false promises, gassing, and assaulting them. Their bodies were hidden in a small alcove in the kitchen wall, sealed with wallpaper.

Discovery and arrest

By early 1953 Christie abandoned 10 Rillington Place, leaving the flat to new tenants. On 24 March 1953, the new occupant, Beresford Brown, discovered human remains during renovations. Police quickly uncovered the three women in the alcove, Ethel under the floorboards, and the earlier skeletal remains in the garden.

Christie, now on the run, drifted through London lodging houses. A nationwide manhunt followed, but Christie seemed curiously passive. On 31 March 1953, a policeman spotted him near Putney Bridge and arrested him without resistance.

The trial at the Old Bailey

Christie was charged with the murder of his wife, Ethel, though evidence of the others was introduced. His trial opened at the Old Bailey on 22 June 1953, before Mr Justice Finnemore.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Christie had killed at least seven women using a consistent modus operandi.

-

Forensic evidence and confessions tied him to the murders.

-

His lies about Evans and Beryl highlighted his manipulative nature.

The Defence’s case:

-

His counsel attempted an insanity plea, citing Christie’s sexual sadism, history of violence, and disturbed childhood.

-

Psychiatric experts, however, testified that Christie was a classic psychopath who understood his actions.

Christie himself testified in a monotone, describing murders with chilling detachment. The press noted his eerie calm, in stark contrast to the brutality of his acts.

Verdict and execution

The jury deliberated for less than an hour before finding Christie guilty of murder. He was sentenced to death and executed at Pentonville Prison on 15 July 1953, just weeks after his trial. Like Evans before him, he faced Albert Pierrepoint on the scaffold.

Historical impact

The Christie case, intertwined with Evans’, had enormous consequences:

-

Exposure of miscarriage of justice: Christie’s conviction proved that Timothy Evans had almost certainly been innocent. Public outrage surged, shaking confidence in the justice system.

-

Death penalty debate: The Evans-Christie saga became central to the abolitionist campaign, showing that capital punishment could not be reversed once miscarriages occurred. Evans was posthumously pardoned in 1966.

-

Policing reform: The failures of the Metropolitan Police in investigating 10 Rillington Place, their credulous acceptance of Christie’s testimony, and their coercion of Evans highlighted systemic flaws. Calls for better investigative training and oversight grew louder.

-

Cultural resonance: The house itself became a symbol of hidden horror in ordinary streets. Books, films, and television dramas—most notably 10 Rillington Place (1971), starring Richard Attenborough as Christie—seared the story into public memory.

Bottom line

Together, the cases of Timothy Evans and John Christie expose the darkest paradox of justice: that the innocent can be condemned while the guilty live on. Evans’ execution remains a haunting miscarriage, while Christie’s trial revealed the depth of horror concealed by a mild-mannered exterior. Their intertwined legacies helped drive the campaign that ultimately abolished the death penalty in Britain, leaving 10 Rillington Place not just as a crime scene but as a permanent warning about fallibility, injustice, and the cost of human error.

7) John Bodkin Adams (1957)

Background: the doctor of Eastbourne

John Bodkin Adams was born in 1903 in Randalstown, County Antrim, Northern Ireland, into a devoutly Protestant family. His father was a preacher in the Plymouth Brethren, and the young Adams was raised within a rigid moral framework. After medical training at Queen’s University Belfast, he qualified as a physician in 1922 and eventually settled in Eastbourne, Sussex, a genteel seaside town popular with retirees and the wealthy elderly.

By the 1930s, Adams had built a thriving private practice. He cultivated a reputation as attentive and obliging, especially with elderly female patients of means. He was known for making house calls at all hours, prescribing liberally, and offering comfort and companionship. He also became the beneficiary of an unusually high number of wills: by the mid-1950s, it was estimated that over 130 of his patients had remembered him in their wills, and more than 100 had died under his care. Some left him substantial sums, antiques, or even cars. Rumours swirled, but nothing stuck.

Adams moved in respectable circles, attending church regularly, playing the part of an upstanding GP. Yet behind the façade lurked growing suspicion: too many patients had died too conveniently, often after being administered large, frequent doses of morphine and heroin.

Suspicion builds

In 1956, the death of Edith Alice Morrell, a wealthy 81-year-old widow, reignited whispers. Adams had attended her in her final days, administering copious painkillers. She had changed her will to leave him a Rolls-Royce. Another patient, Gertrude Hullett, a 50-year-old widow, died after heavy sedation by Adams. Local gossip, amplified by colleagues, began to attract official attention.

Police quietly launched an investigation, interviewing nurses and examining prescription records. They were shocked at the pattern: Adams prescribed vast quantities of controlled drugs, often without clear medical justification, and many patients had died shortly after receiving his care. He was arrested in December 1956, creating a national sensation.

The trial at the Old Bailey

Adams was charged not with dozens of killings, but with a single count: the murder of Mrs Morrell, who had died in 1950. Prosecutors, led by Attorney General Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller KC, believed proving one case beyond doubt would be enough to secure conviction and potentially open the door to further charges. The trial opened on 18 March 1957 at the Old Bailey, presided over by Mr Justice Devlin.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Adams had deliberately overdosed Mrs Morrell with morphine and heroin, shortening her life for his own benefit.

-

Witnesses, including nurses, testified to his administration of unusually large doses and his unorthodox, secretive behaviour.

-

The motive: Mrs Morrell had remembered him in her will, gifting him a Rolls-Royce and other items.

The Defence’s case:

-

Adams’ lead counsel, Sir Frederick Geoffrey Lawrence QC, argued that Mrs Morrell was terminally ill and in great pain. Morphine and heroin were common palliative treatments at the time.

-

There was no direct proof that Adams intended to kill; at worst, he may have erred in judgement in trying to relieve suffering.

-

They suggested Adams had been singled out because of gossip and envy, not evidence.

Adams himself cut an unassuming figure in court: quiet, pale, deferential. Unlike flamboyant killers such as Haigh or Christie, Adams seemed dull, even banal. That blandness may have worked in his favour.

Verdict and acquittal

After a three-week trial, the jury deliberated for just 45 minutes. On 15 April 1957, Adams was acquitted of murder. He wept with relief. Further charges relating to other patients were quietly dropped. Instead, he was convicted only of minor prescription irregularities and fined. Adams returned to Eastbourne, where he lived quietly until his death in 1983.

Why the trial caused outrage

The Adams trial created enormous controversy. Many observers were convinced of his guilt; suspicions suggested he may have killed more than 160 patients. Yet the Crown failed to secure even one murder conviction. Several factors contributed to the outrage:

-

The difficulty of proving intent in “mercy killing” cases: In the 1950s, palliative care was poorly regulated. Doctors often prescribed morphine freely at the end of life. The line between easing suffering and hastening death was blurred.

-

Establishment protection?: Rumours persisted that Adams was shielded by the medical and legal establishment. The Attorney General was criticised for handling the case badly. His cross-examinations were weak, and the Crown’s case relied heavily on inference. Some believed authorities feared a guilty verdict would destabilise public trust in doctors.

-

Public perception: Many could not fathom that such a quiet, respectable GP could be a mass murderer. Others thought he represented the archetype of the “angels of death” phenomenon—medical professionals who exploit trust to kill.

Historical impact

The Adams case had a profound legacy:

-

Medical ethics: The trial forced Britain to confront the uncomfortable overlap between medical care and euthanasia. It spurred debates about the “double effect” principle—when a doctor administers pain relief knowing it may also shorten life.

-

Law reform: Though Adams escaped conviction, his case highlighted the need for stricter regulation of controlled substances and clearer guidelines for end-of-life care.

-

Public mistrust: For years, Eastbourne lived under the shadow of suspicion. Adams’ patients had nicknamed him “Doctor Death.” After his acquittal, the press portrayed him as a sinister figure who had gamed the system.

-

Cultural echoes: The Adams affair became a touchstone for discussions about professional privilege. Was he saved by sloppy prosecution, or by a system reluctant to convict one of its own?

Bottom line

John Bodkin Adams remains one of Britain’s most enigmatic figures: the GP who may have been history’s most prolific serial killer, or perhaps a doctor unfairly maligned for doing what many of his peers quietly did. His acquittal remains one of the most controversial verdicts in British legal history. Whether guilty of mass murder or not, Adams forced Britain to confront the uneasy boundary between medical care and medical killing—a boundary that continues to trouble courts and ethics boards to this day.

8) Peter Sutcliffe – “The Yorkshire Ripper” (1981)

Background: an unremarkable man in plain sight

Peter William Sutcliffe was born in Bingley, West Yorkshire, in 1946, into a working-class Catholic family. His early life was outwardly ordinary: he was quiet, somewhat withdrawn, and did not excel at school. As a teenager he drifted between jobs—grave-digger, lorry driver, factory worker. Yet, beneath the surface, Sutcliffe was developing troubling fixations. He was fascinated by sex workers and harboured violent fantasies, fuelled by feelings of inadequacy and resentment.

By the 1970s, Sutcliffe had married Sonia Szurma, a teacher-in-training. Their marriage was unconventional: Sonia was controlling, sometimes volatile, while Sutcliffe remained passive but secretive. They lived in modest suburban homes in Bradford and later Heaton, where neighbours considered him unremarkable. He was attentive to Sonia, held steady jobs, and appeared, to many, dull.

But from 1975 onwards, Sutcliffe began a campaign of terror that would grip northern England for five years.

The murders begin

His first acknowledged murder was Wilma McCann, a 28-year-old mother of four, killed near her Leeds home in October 1975. She had been struck with a hammer and stabbed repeatedly. The brutality shocked police, but there was little to identify the killer.

In January 1976, he struck again, murdering Emily Jackson, a 42-year-old part-time sex worker, lured into his car and killed with hammer blows and screwdriver stabs. Over the next two years, Sutcliffe attacked several more women—some sex workers, some simply walking home at night. His weapons were simple but devastating: hammers, screwdrivers, knives.

By 1977, the press had dubbed him the “Yorkshire Ripper,” drawing comparisons to Jack the Ripper nearly a century earlier. Panic spread across Leeds, Bradford, Manchester, and Sheffield. Women were warned not to go out alone at night. The killings were characterised by frenzied violence, mutilation, and apparent sexual overtones.

A city under siege

Sutcliffe’s victims were not confined to sex workers, as police initially assumed. Among them were Jayne MacDonald, a 16-year-old shop assistant murdered in Leeds in June 1977, and Barbara Leach, a 20-year-old student killed in Bradford in 1979. The indiscriminate nature of the attacks created widespread fear: any woman could be next.

Meanwhile, Sutcliffe maintained a double life. He continued working as a lorry driver, living quietly with Sonia, and visiting his parents. Friends described him as odd but harmless. He played the role of dutiful husband while secretly feeding a compulsion to kill.

The hoax that derailed the investigation

In 1979, West Yorkshire Police received letters and a tape recording from a man claiming to be the Ripper. The tape, sent to Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield, taunted police in a Wearside accent. Convinced it was genuine, detectives diverted enormous resources to Sunderland and the North East, sidelining other leads.

The real Ripper, however, was Sutcliffe—who lived and worked in Yorkshire. The “Wearside Jack” hoax, later unmasked as the work of John Humble, disastrously misdirected the investigation. Sutcliffe continued killing during this period, taking advantage of police fixation on the false lead.

Capture at last

On 2 January 1981, Sutcliffe was finally arrested—almost by chance. Police in Sheffield stopped him for driving with false number plates. In custody, officers noticed he matched the Ripper’s description and bore similarities to a composite sketch. During questioning, Sutcliffe broke down and confessed to being the Yorkshire Ripper. He calmly detailed his attacks and murders, eventually admitting to 13 murders and seven attempted murders between 1975 and 1980.

The trial at the Old Bailey

Sutcliffe’s trial opened at the Old Bailey on 5 May 1981, before Mr Justice Boreham. Public anticipation was enormous. Britain had lived under the shadow of the Ripper for half a decade; now the man himself sat in the dock.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Sutcliffe had confessed in detail, matching forensic evidence and witness accounts.

-

Victims’ injuries, weapons, and timelines corroborated his statements.

-

There was no doubt Sutcliffe had committed the crimes.

The Defence’s case:

-

Sutcliffe’s lawyers argued he was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. They claimed he heard voices from God commanding him to kill sex workers as part of a divine mission.

-

Psychiatric experts supported diminished responsibility, suggesting he should be convicted of manslaughter on medical grounds.

The trial became a battle between psychiatry and the prosecution. Sutcliffe himself appeared calm, almost detached, describing his crimes without emotion. He insisted his actions were compelled by voices, but the sheer planning—carrying weapons, choosing secluded spots, evading police—suggested otherwise.

Verdict and sentence

The jury rejected diminished responsibility. On 22 May 1981, Sutcliffe was convicted of 13 counts of murder and seven counts of attempted murder. He was sentenced to 20 concurrent life sentences, later converted to a whole life tariff. He was imprisoned at Parkhurst and later Broadmoor Hospital, where he remained until his death in 2020.

Public and political fallout

The Sutcliffe case left scars far beyond the crimes themselves:

-

Policing failures: West Yorkshire Police had interviewed Sutcliffe nine times during the investigation but failed to connect the dots. Obsession with the hoax tape and sexism within the force—downplaying victims who were sex workers—meant opportunities were missed. A damning report by Sir Lawrence Byford later catalogued these failures.

-

Sexism and victim-blaming: Police appeals urged “innocent women” not to go out at night, implicitly stigmatising those who were sex workers. Feminist groups organised protests under the banner “Reclaim the Night,” arguing that women should not be confined because of male violence.

-

Fear and trauma: The killings left a generation of women in northern England living under curfews of fear. Parents restricted daughters’ movements, and nightlife dwindled. The “Yorkshire Ripper” became shorthand for the terror of random, misogynistic violence.

-

Cultural impact: Books, documentaries, and dramatizations—such as the BBC’s The Ripper (2020)—ensured Sutcliffe’s crimes remain etched in British cultural memory. He became a grim symbol of serial killing, alongside figures like Jack the Ripper and Ted Bundy.

Bottom line

Peter Sutcliffe was not the first British serial killer of the 20th century, but he was among the most terrifying. His ability to blend into ordinary life while waging a campaign of misogynistic violence unsettled the nation. The investigation’s failures exposed deep flaws in policing, particularly regarding women’s safety and credibility. His trial and conviction closed a chapter of terror, but the debates it provoked—about justice, gender, and institutional blindness—continue to resonate. The Yorkshire Ripper left not just victims, but also a society forced to confront its own prejudices and vulnerabilities.

9) Dennis Nilsen (1983)

Background: the lonely man who wanted company

Dennis Andrew Nilsen was born in Fraserburgh, Scotland, in 1945, the second of three children. His childhood was marked by instability: his father, a Norwegian soldier, abandoned the family early, and his mother remarried. Nilsen grew up quiet, withdrawn, and deeply affected by the death of his beloved grandfather, whose open coffin he was forced to view as a child. Later, he would recall this moment as formative, blending mortality, intimacy, and control into his developing psychology.

After leaving school, Nilsen joined the British Army in 1961 and served for 11 years as a cook. He was described as competent but aloof. Stationed in Aden, West Germany, and Cyprus, he gained skills in butchery and dissection—knowledge that would later take on a chilling significance. He left the army in 1972, drifting into police training (which he soon abandoned), then civil service jobs in London.

By the mid-1970s, Nilsen had settled into a routine life in London’s gay community, living quietly in flats and working as a job centre clerk. Outwardly, he was unremarkable: tall, bespectacled, articulate, and somewhat pompous. But he was plagued by isolation and an obsessive fear of abandonment. His solution—both grotesque and tragic—was to kill men he lured to his home so that they would never leave.

The murders begin

Nilsen’s first known murder occurred on 30 December 1978, when he invited a young man, Stephen Holmes, back to his flat at 195 Melrose Avenue, Cricklewood, after drinking at a pub. The next morning, fearful of losing his company, Nilsen strangled Holmes and kept the body in his flat, bathing and sleeping beside it before eventually burning it in the garden.

Between 1978 and 1981, Nilsen killed at least 12 young men, most of them homeless, drifters, or men he met in pubs. He would offer them food, drink, or a place to stay, before strangling them with a tie or garroting them during the night. The bodies were then stored under floorboards, in cupboards, or dismembered. In the Melrose Avenue flat, he burned remains in a bonfire mixed with tyres to mask the smell.

In 1981, he moved to 23 Cranley Gardens, Muswell Hill. Lacking a garden for disposal, he boiled flesh from bones, flushed organs down the toilet, or stored limbs in cupboards. Neighbours occasionally complained of foul odours, which Nilsen explained away.

Discovery and arrest

Nilsen might have continued indefinitely but for a mundane plumbing problem. In February 1983, tenants at Cranley Gardens complained of blocked drains. A plumber, upon inspecting the system, discovered a mass of human flesh and bones. Police were called. When officers confronted Nilsen, he appeared calm and resigned. He simply said: “It’s a long story, it goes back a long time.”

At the police station, Nilsen confessed with chilling candour. Over hours of interviews, he detailed 15 murders, providing dates, methods, and the ways he disposed of bodies. He appeared detached, describing the killings as acts to satisfy loneliness rather than sadistic urges.

The trial at the Old Bailey

Nilsen’s trial opened on 24 October 1983 at the Old Bailey, before Mr Justice Croom-Johnson. It quickly became one of the most sensational trials of the decade, attracting both media and public fascination.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Nilsen had confessed to multiple murders, providing details only the killer could know.

-

Forensic evidence corroborated his accounts: remains were found in his flats, including skulls, torsos, and dissected limbs.

-

Witnesses testified about Nilsen’s pattern of picking up vulnerable young men.

-

The sheer number of victims demonstrated premeditation and a pattern of homicidal behaviour.

The Defence’s case:

-

Nilsen’s lawyers argued diminished responsibility, citing severe personality disorder and borderline psychosis. They claimed he killed not out of malice but from compulsion rooted in loneliness and fear of abandonment.

-

Psychiatric experts described Nilsen as obsessed with retaining control over companions, blurring the line between life and death in his mind.

Nilsen himself testified in lengthy, often self-indulgent fashion, portraying himself as a tragic figure who killed to avoid being alone. He spoke with a mixture of arrogance and detachment, angering some jurors and fascinating the press.

Verdict and sentence

On 4 November 1983, the jury rejected diminished responsibility. Nilsen was convicted of six counts of murder and two counts of attempted murder. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a recommendation that he serve a minimum of 25 years. In 1994, Home Secretary Michael Howard imposed a whole-life tariff, ensuring he would never be released.

Nilsen spent the rest of his life in prison, writing voluminous diaries and corresponding with criminologists. He died in 2018, aged 72, from complications following surgery.

Historical impact

The case of Dennis Nilsen reverberated across Britain:

-

Conversations about sexuality: Nilsen’s homosexuality, though incidental to his crimes, was sensationalised by the press. At a time when gay men still faced discrimination, his case reinforced harmful stereotypes, sparking debates about how the media framed sexuality in crime reporting.

-

Policing and missing persons: Many of Nilsen’s victims were never formally reported missing. They were homeless, estranged from families, or living transient lives. His case highlighted the invisibility of marginalised young men and the lack of systems to track missing persons.

-

Psychology of serial killers: Nilsen’s confessions became a rich resource for criminologists studying necrophilia, compulsion, and the link between loneliness and violence. Unlike sadistic killers, Nilsen insisted he derived little sexual pleasure from murder itself—rather, from the presence of a passive, unresisting companion.

-

Public horror: The details—dismembered bodies in cupboards, flesh boiled in pots, organs flushed down toilets—were almost beyond comprehension. They cemented Nilsen’s place as one of Britain’s most grotesque killers.

-

Cultural echoes: Nilsen inspired books, plays, and documentaries, most recently the 2020 drama Des, with David Tennant portraying him. The case remains a benchmark for public fascination with serial murderers who appear outwardly ordinary.

Bottom line

Dennis Nilsen was not a killer driven by greed or sadism, but by a warped solution to loneliness. His murders were as much about possession as destruction: he killed to keep, not to eliminate. That distinction horrified Britain all the more. His trial forced society to confront the vulnerability of those on its margins and the terrifying possibility that an articulate, mild-mannered man could harbour such grotesque compulsions. Nilsen’s case remains one of the most disturbing chapters in British criminal history, a study in how isolation and fantasy can metastasise into atrocity.

10) Ian Brady & Myra Hindley – The Moors Murders (1966 trial, later appeals)

Background: two lives that converged in darkness

Ian Brady was born in Glasgow in 1938, the illegitimate son of a waitress. Raised in foster care, he developed a reputation as intelligent but difficult, prone to violent temper and disturbing fantasies. As a teenager, he immersed himself in Nietzsche, de Sade, and Nazi ideology. By the time he moved to Manchester in 1955, Brady was a brooding loner, working menial jobs and nurturing sadistic fantasies of domination and control.

Myra Hindley, born in Gorton, Manchester in 1942, grew up in a working-class Catholic family. Described as a tomboy in childhood, she was bright but unremarkable at school. Her early life was marked by a strict father who instilled both toughness and submission to authority. Hindley was searching for identity and purpose when she met Brady in 1961 while working as a typist at Millwards Merchandising.

Their meeting was fateful. Hindley was drawn to Brady’s dark charisma, his talk of sadism, Nazism, and transgression. Under his influence, she dyed her hair peroxide blonde, began carrying a hunting knife, and absorbed his violent fantasies. Together, they formed one of the most infamous partnerships in British criminal history.

The crimes

Between 1963 and 1965, Brady and Hindley abducted, tortured, and murdered at least five children and teenagers around Manchester:

-

Pauline Reade (16): abducted on her way to a dance in July 1963.

-

John Kilbride (12): lured from a market in November 1963.

-

Keith Bennett (12): abducted while visiting his grandmother in June 1964.

-

Lesley Ann Downey (10): taken from a fairground on Boxing Day 1964.

-

Edward Evans (17): lured and killed in October 1965.

Brady and Hindley buried several of their victims on Saddleworth Moor, giving the case its enduring name: the Moors Murders. The crimes were sadistic, involving sexual assault, torture, and humiliation. In the case of Lesley Ann Downey, a tape recording was made of her final moments—a detail that horrified Britain when revealed at trial.

Discovery and arrest

The pair’s downfall came in October 1965. Brady had invited David Smith, Hindley’s brother-in-law, to witness the murder of Edward Evans. Smith, horrified, reported the killing to police. When officers searched Brady and Hindley’s home, they found evidence linking them to other disappearances, including photographs of Saddleworth Moor. Excavations revealed the graves of Pauline Reade and John Kilbride.

The trial at Chester Assizes

The trial opened on 19 April 1966 at Chester Crown Court before Mr Justice Fenton Atkinson. Public interest was overwhelming; press coverage painted Brady and Hindley as embodiments of evil.

The Prosecution’s case:

-

Brady and Hindley were charged with the murders of Edward Evans, Lesley Ann Downey, and John Kilbride.

-

The tape recording of Lesley Ann’s torture, played in court, left jurors and journalists visibly shaken. Hindley’s voice was heard scolding the child, while Brady’s voice directed the abuse.

-

Photographs of Hindley with her dog on Saddleworth Moor were matched with locations where bodies were buried.

-

David Smith testified as eyewitness to Edward Evans’ murder.

The Defence’s case:

-

Brady claimed Smith was lying and tried to implicate him.

-

Hindley denied knowledge of the murders, portraying herself as under Brady’s control and unaware of his true actions.

-

Both defendants attempted to distance themselves from the worst evidence.

The jury was unconvinced. Brady was convicted of all three murders; Hindley of two (Downey and Evans). Both received life sentences, the maximum penalty after the abolition of the death penalty for murder in 1965.

Imprisonment and later revelations

Over the decades, the Moors Murders retained a grim hold on Britain. Brady was transferred to Ashworth psychiatric hospital, where he remained until his death in 2017. He styled himself as a Nietzschean intellectual, refusing rehabilitation, embarking on hunger strikes, and publishing self-serving writings. Hindley, meanwhile, became the focus of public hatred as the “most hated woman in Britain.” Her repeated appeals for parole—citing coercion by Brady—were fiercely opposed. She died in prison in 2002.

In the years after their conviction, police learned more: Brady admitted to additional murders, including Keith Bennett, whose body has never been found despite repeated searches on the moor. Bennett’s mother, Winnie Johnson, campaigned tirelessly until her death in 2012 for the recovery of her son’s remains.

Historical and cultural impact

The Moors Murders seared themselves into British consciousness for several reasons:

-

The victims’ ages: The youth and innocence of the victims amplified the horror. These were children and teenagers, murdered with unimaginable cruelty.

-

The tape recording: The Lesley Ann Downey tape remains one of the most disturbing pieces of evidence ever presented in a British courtroom. Its existence cemented Hindley’s infamy.

-

Media demonisation: Hindley’s peroxide blonde image became iconic, reproduced endlessly as a symbol of female evil. Her gender made her the focus of particular vilification, often eclipsing Brady in public outrage.

-

Impact on sentencing policy: Their refusal to reveal burial sites spurred debate about whole-life tariffs and justice for families. Brady’s hunger strikes and legal battles over force-feeding further complicated the issue of prisoners’ rights.

-

Cultural legacy: The case inspired books, films, plays, and songs—sometimes controversially, such as The Smiths’ “Suffer Little Children.” The story remains shorthand for unspeakable evil in modern British culture.

-

Public memory: For decades, the names Brady and Hindley were invoked in headlines to represent monstrosity. They became cultural archetypes of the sadistic killer couple, symbols of cruelty and corruption of innocence.

Bottom line

The Moors Murders were not just crimes; they were a cultural earthquake. Brady and Hindley shattered the illusion of childhood safety, transforming Saddleworth Moor into a haunted landscape in Britain’s imagination. Their trial exposed the depths of human cruelty and the inadequacy of language to describe it. Even decades later, the names Brady and Hindley evoke horror, rage, and grief. Their case reshaped the way Britain thought about evil, punishment, and the enduring scars left by crime.

Conclusion

Murder trials are not only reckonings for the accused, they are also mirrors held up to the societies that conduct them. Across the twentieth century, Britain’s most infamous trials exposed far more than the details of crime scenes—they revealed the anxieties, prejudices, and aspirations of an evolving nation.

Dr Crippen’s 1910 conviction showcased the dawn of modern forensics and the global reach of wireless technology. Edith Thompson’s fate in 1923 laid bare a society quick to conflate passion with pathology and condemn a woman for her desires. Neville Heath and John George Haigh, charming predators of the 1940s, embodied post-war fears of respectability masking monstrous violence. Timothy Evans and John Christie’s intertwined tragedies at 10 Rillington Place revealed the catastrophic cost of police error and helped drive the eventual abolition of the death penalty.

The case of John Bodkin Adams blurred the line between care and killing, forcing Britain to confront unsettling questions about medicine, privilege, and proof. In the late century, the reigns of terror carried out by Peter Sutcliffe and Dennis Nilsen reflected deeper fault lines: the invisibility of the vulnerable, the institutional sexism that stifled policing, and the alienation of modern urban life. Finally, the Moors Murders of Brady and Hindley seared themselves into national consciousness as the embodiment of unthinkable cruelty, a crime whose cultural reverberations continue to echo.

Taken together, these ten trials mark milestones in the history of British justice. They highlight advances in forensic science, expose the dangers of wrongful conviction, and demonstrate how public outrage and media coverage can shape both verdicts and memory. More than anything, they remind us that the courtroom is not only a place of judgement but also a stage upon which society negotiates its values.

Each of these cases remains haunting because they are more than stories of killers—they are stories about how Britain responded, how it failed, how it changed. They reveal that justice is fragile, fallible, and always evolving. And they serve as enduring warnings: that truth can be obscured by prejudice, that evil can hide in plain sight, and that the lessons of history are written not just in law books, but in the lives cut short and the trials that followed.